Learning About Churning: How Diminished Labor Market Churn Is Consistent With a Solid Labor Market

Payroll grew by a stronger-than-expected 256,000 last month and the unemployment rate ticked down to 4.1%; the jobless rate has fluctuated between 3.9% and 4.2% since April 2024. For the year of 2024, average job gains were a solid 186,000, and the average unemployment rate was a low 4.0%. Wage growth came in at 3.9% in 2024, and while we do not have inflation data yet for December, it is surely the case that December was the 20th month in a row that wage growth beat price growth.

These data characterize a labor market that remains in solid shape, with low unemployment, strong labor market participation, and wage growth that is consistently beating price growth, implying increased buying power from an hour of work. However, it is also clear that the labor market has cooled over the last year and a half. The three-month average of monthly job gains has slowed from 242,000 in July 2023 to 170,000 in December 2024. The unemployment rate is up 70 basis points from 3.4% in April 2023.

One important dimension of the cooler job market is diminished churn, meaning smaller flows from one job-market status (or from one job) to another. In other words, people have become less likely to make labor market moves.

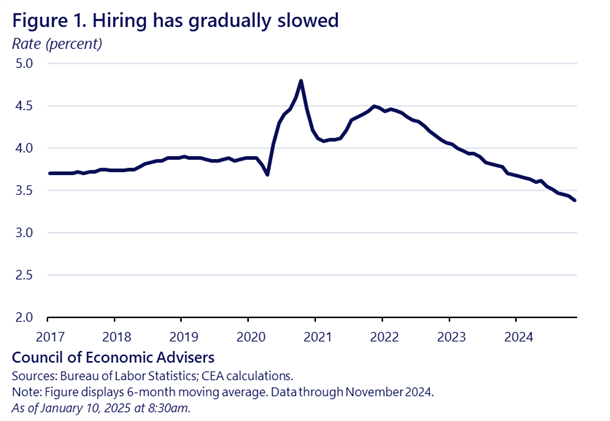

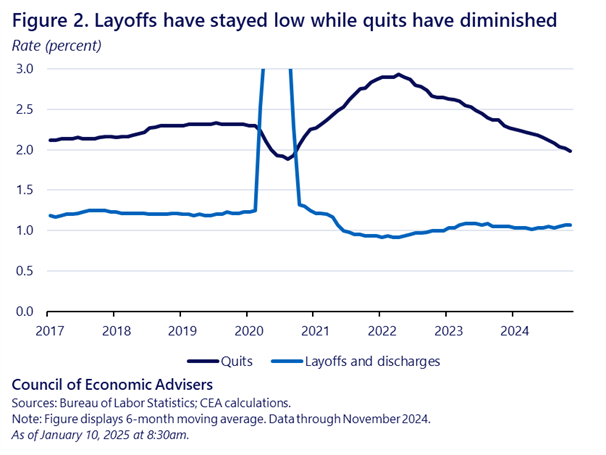

Figure 1 shows how hiring has diminished as a result of reduced flows from non-employment to employment or from job to job. This recent trend coexists with a flat layoff rate and a falling quit rate, as shown in Figure 2 (the scale cuts out the outlier pandemic observations so as to more clearly see relevant trends). A broadly consistent pattern is evident in unemployment claims data: initial claims have held low and steady while continued claims have been somewhat elevated. Recent media reports have noted some of these dynamics, as in this article focusing on longer unemployment durations.

How concerning are these developments? Over the long run, labor market dynamism—including job switching and occupational upgrading—is important for both workers and the broader economy. But as our assessment of current labor market conditions reveals, we believe diminished hiring is still consistent with a solid labor market. Layoffs have remained low and quits have fallen, offsetting a declining hiring rate. The hiring rate has been strong enough to keep unemployment relatively low and prime-age labor force participation near an historically high level.

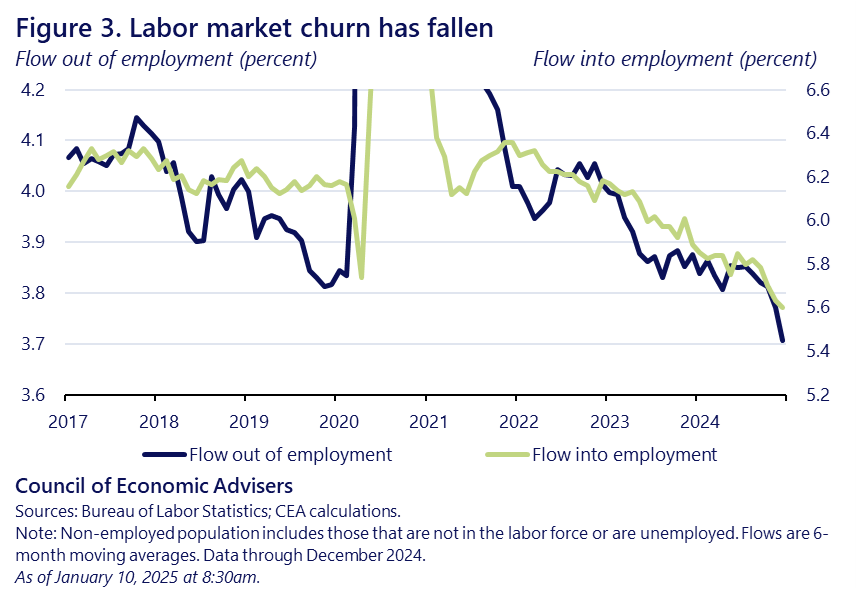

A clear way to see the offsetting declines in labor flows is to graph the flow rates from employment to non-employment, and vice versa. A robust job market can be characterized by lower flows both into employment (lower hiring) and out of employment (fewer layoffs). Figure 3 shows just that using data from the Current Population Survey. In recent years, fewer workers have left employment, and fewer of the non-employed have become employed.

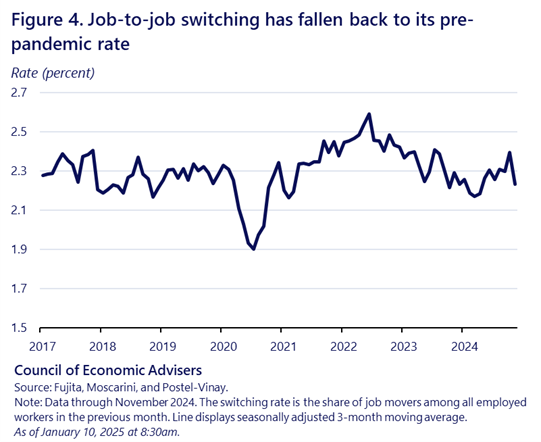

In some cases, dynamism indicators are down, but they’re back to pre-pandemic levels rather than flashing red. Figure 4 (which reproduces calculations from the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia) shows an example: job-to-job transition rates. These are down from 2022 highs and now sit at a more normal level.

Why has churn declined in the recent past? One reason is simply that the very tight labor market of 2022 was not sustainable, and necessary cooling has followed as labor supply and demand settle at more normal levels. Another reason is rooted in the unique dynamics of the post-pandemic recovery: the rise in remote work led to a surge in worker reallocation to jobs offering that option. Chapter 2 of the 2025 Economic Report of the President, out today (!), devotes a chapter to the economic implications of remote work. Other potential reasons for diminished labor market churn, like demographic shifts (an older workforce tends to have less churn) or the rise in occupational licensing, tend to play out over longer time horizons.

For now, lower churn—though leading to longer job searches and unemployment spells—does not signal a broader deterioration in economic conditions. As noted, most of the relevant trends are settling back into more normal levels, and the absence of higher layoffs is a key signal of a healthy labor market health. Moreover, GDP growth, consumer spending, and investment are all consistent with ample job creation and a robust economy.

Still, these developments bear watching. The persistently strong labor market has long been one of the key drivers of the current expansion. If weaker hiring leads to substantially higher unemployment, that would be a signal that the labor market has overly cooled.