Improving Access to Unemployment Insurance

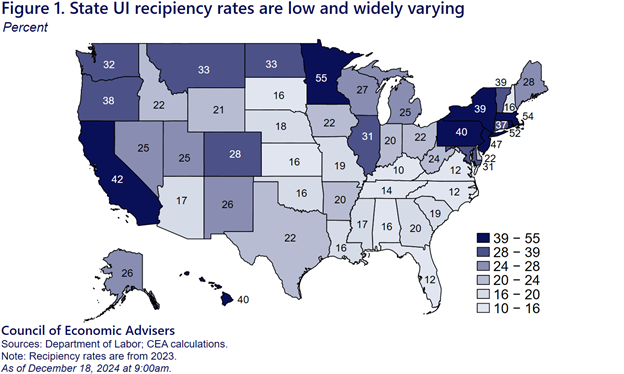

Unemployment insurance (UI) is the core support for workers who lose their jobs through no fault of their own and might struggle to make ends meet while they find a new one. It is also a key support for the economy during difficult times, ensuring that unemployed workers have temporary income support that shores up both their own finances and consumer spending broadly. But for UI to be effective in these roles, it must actually reach unemployed workers while they are searching for new jobs. Many unemployed workers do not receive UI, with wide differences in recipiency rates between states like Minnesota (55%) or Massachusetts (54%) and states like North Carolina (12%) and Kentucky (10%). Overall, less than a third of unemployed workers in the U.S. receive UI benefits.[1]

What accounts for the wide differences across states? One possibility is that states vary systematically in the shares of their workers who are eligible according to standard requirements for applicants like having been laid off (rather than quitting, for example) and not yet having exceeded 26 weeks of unemployment.

However, CEA finds that differences in those shares account for little of recipiency rate gaps across states. Rather, choices by states about how many weeks of benefits to provide (which currently range as low as 12 weeks in some states) are associated with a portion of differences in recipiency rates. And most of the differences across states are driven by other factors entirely, including state policy choices about how accessible to make their UI systems. Substantial opportunities exist to improve workers’ access to UI, some of which are already being undertaken by the Biden-Harris Administration.

What is UI recipiency and why does it vary so much?

Unemployment benefits, which temporarily replace a portion of the worker’s prior wages, are funded through taxes on employers and generally available only to workers who are laid off (without cause) and who are actively searching for a new job. Because UI is a joint federal-state program, each state has its own rules and approach, operating within the federal UI framework.

The Department of Labor defines UI recipiency as the share of total unemployed, as measured in the Current Population Survey (CPS), who currently receive UI benefits. The recipiency rate is far lower than 100% in every state, and for the entire country is just under 30%. See Figure 1 for each state’s recipiency rate in 2023.

Part of the reason for low recipiency is that many unemployed workers are not eligible for UI benefits. This could be for several reasons: they might have exhausted their benefits (which cannot exceed a state-determined number of weeks), quit their jobs (rather than being laid off), or entered the labor force for the first time. They could be self-employed and therefore ineligible. They might also have insufficient earnings or hours history to meet their state’s eligibility requirements.

Another key factor driving low recipiency is lack of take-up among eligible workers. Some potential reasons are unconcerning: a worker might expect to imminently find a new job and determine that UI benefits are unnecessary for them. Other reasons are less benign, especially when they reflect state policy design.[2] For example, it may be difficult to apply for UI because of language barriers. Laid-off workers could have incorrect information about their eligibility. Required reporting of job search could be excessively burdensome. And when the maximum duration and wage replacement rate (both of which vary by state) are relatively ungenerous, the incentive to apply for UI is diminished. In these cases, even if an unemployed worker does get UI, it provides relatively little support.

So why does UI recipiency vary so much across states—from 55% (Minnesota) to 10% (Kentucky)? Is it differences in the mix of unemployed workers (e.g., the share in a given who have been laid off), or differences in state policy choices that affect eligibility and take-up? It is possible to explore this to some extent using CPS microdata that describe worker characteristics relevant to UI eligibility. Those data do not include every detail relevant to eligibility, but two key distinctions can be made: between those laid off and other unemployed (like job quitters), and between the short- and long-term unemployed. In general, only workers who are laid off can receive UI, and benefits eligibility is often exhausted after 26 weeks of receipt. These limitations are two of the key eligibility criteria for UI apart from required earnings and/or hours history.[3]

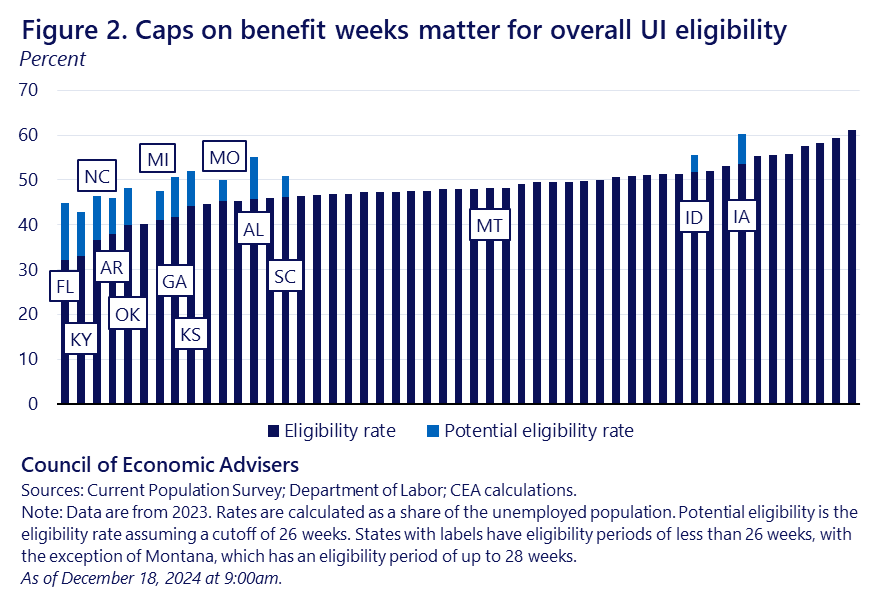

To abstract from state policy choices, CEA first calculates eligibility rates as if every state were to cut off benefits at 26 weeks of unemployment duration—which is not actually the case everywhere. The light blue bars of Figure 2 show the result of this calculation. Specifically, those bars represent the CEA-estimated “potential” eligibility rate for each state, which assumes that laid-off workers who have been unemployed for 26 weeks or less are eligible for UI.[4] Potential eligibility is not especially correlated with the recipiency rate shown in Figure 1. Differences in estimated potential eligibility—assuming a universal benefit cutoff of 26 weeks—explain just 11% of state recipiency-rate variation.

But as noted, states do differ in the maximum number of weeks they provide to UI recipients. Over time, an increasing number of states have reduced that maximum below the standard 26 weeks. The dark blue bars of Figure 2 are estimates of eligibility using the actual maximum number of weeks provided by each state (as of December 2023). Even with this realistic feature, the calculation of eligibility is a rough approximation and could be higher or lower than the true eligibility rate, depending on variation in state rules (e.g., about required earnings history) and other factors not modeled here.[5]

Using actual state maximums, estimated eligibility rates do more to explain state gaps in recipiency rate, accounting for 29 percent of recipiency variation. In other words, states with low recipiency rates tend to be states that have implemented maximum benefits cutoffs below 26 weeks.

However, most variation in recipiency remains unexplained by this analysis. Other factors that states can determine, including the accessibility of their UI systems, are important to address through analysis and policy.

What will it take to improve UI access?

The Biden-Harris Administration has articulated a set of principles for modernizing and improving unemployment insurance. Those principles include ensuring adequate duration of benefits and improving program integrity and access, all of which are necessary for helping UI to function as intended.

One reason for limited access to UI is the difficulty that applicants often have understanding the program and applying for benefits. The Administration is addressing this issue in part by disseminating best practices. A key feature of this effort is the Equitable Access Toolkit and associated outreach and training by the Department of Labor. In addition to helping states prevent UI overpayments, the toolkit shows how to improve applicants’ digital experience, how to unpack where applicants may be abandoning their claims midway through the process, and a variety of other avenues for improving access. Plain language improvements are a special point of emphasis: getting this right can help applicants while also reducing applicant and agency mistakes.

Alongside these efforts, DOL has made numerous grants to states that support equitable UI access, including through better language access and improved applicant experience online. For example, the UI Navigator Program, funded through the American Rescue Plan, augmented state efforts to improve access. Recent analysis of Maine’s navigator program suggests that its participants were more likely to apply for and receive UI than comparable unemployed workers in neighboring states.

Many other factors matter for participation in UI. States that are relatively restrictive with their eligibility requirements could loosen those to permit broader UI access. State UI systems would be more accessible to workers if applications were possible in a variety of modes (including mobile) and if the filing process were consistently seamless and straightforward for applicants. The Biden-Harris Administration continues to work for those who lose jobs through no fault of their own, ensuring that they can get back on their feet as quickly and easily as possible.

[1] Here and below, calculations are based on data for 2023, accessed from IPUMS-CPS and the U.S. Department of Labor.

[2] For a comprehensive discussion of related issues, see Wandner (2023).

[3] It is not straightforward with monthly CPS data to accurately adjust for monetary eligibility, e.g., required earnings history, and CEA does not attempt to do so. One paper finds that monetary eligibility requirements are not the primary impediment to access for non-recipients, pointing instead to take-up and non-monetary requirements as the main barriers (Shaefer 2010).

[4] The overall approach to calculating eligibility is similar to that used in Nunn and Ratner (2019). Workers on temporary layoff or whose temporary job ended are also considered eligible, in addition to those who experience involuntary job loss. Unemployed re-entrants present a difficult case, because many of them are workers with brief spells of nonparticipation, generated either by measurement error or brief lapses in job search and availability for work. CEA assumes that re-entrants with recorded unemployment spell duration above 4 weeks but equal to or below the maximum are eligible for UI. CEA also assumes that workers with self-employed status, including independent contractors, are ineligible.

[5] True eligibility rates could be lower than in Figure 2 after taking into account factors like required earnings history. But true eligibility rates could also be lower in states that, for example, extend eligibility to workers who quit for certain specified reasons. More generally, responses to the CPS may not align with administrative data used to determine UI eligibility and recipiency.