December CPI Blog: Updating our Housing Model

Today’s CPI report came in at expectations, as both headline and core inflation were 0.3% in November. On a yearly basis, headline and core inflation were 2.7% and 3.3%, respectively, also at expectations. Core inflation has fluctuated between 3.2-3.4% since May, indicating a slowdown in inflation’s decline. Though the path of disinflation has been bumpy since CPI inflation peaked in June 2022, we expect inflation to continue to trend toward its target.

For more on today’s release, check out CEA’s X thread.

Importance of housing inflation

As inflation has fallen from its peak, housing inflation has remained elevated. The decades-in-the-making structural supply shortfall in the U.S. housing market preceded the pandemic, while pandemic-induced housing demand further exacerbated the misalignment between housing supply and demand.

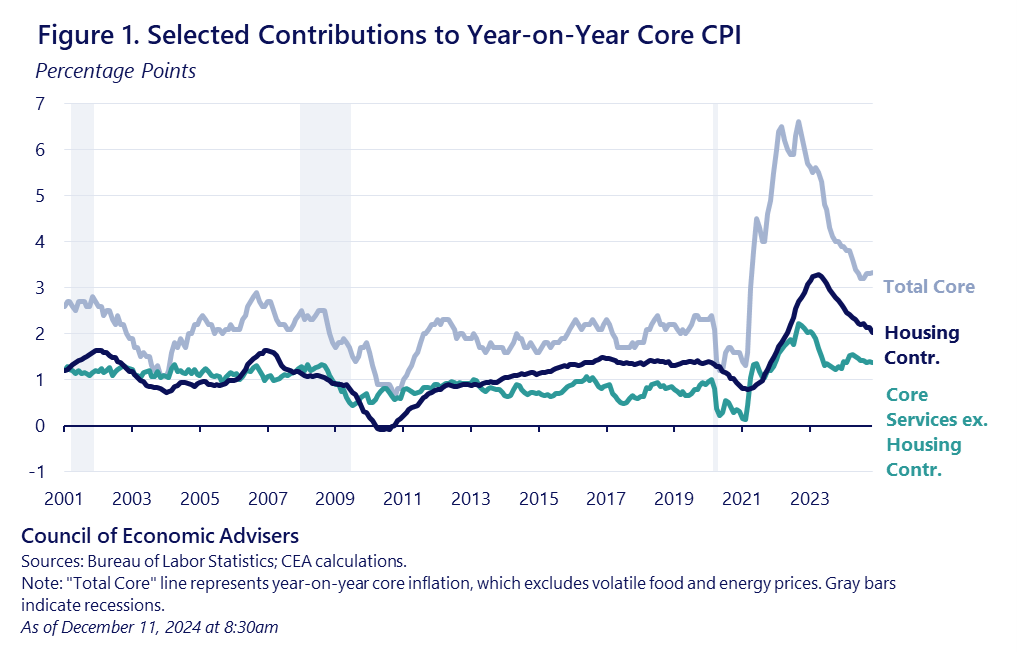

As CEA has previously detailed, housing has played a substantial role in inflation since the second half of 2022. Since the start of 2022, housing inflation has contributed 2.5 percentage points to year-on-year core inflation on average, 1.2 percentage points higher than the 2017—2019 average contribution. In what follows, we discuss the reasons for still-elevated housing price inflation and present an updated model that forecasts how housing inflation might evolve.

Housing inflation—which CEA defines as the combination of rent of primary residence and owners’ equivalent rent (OER)—peaked in April 2023 at 8.3% on a year-on-year-basis and since fallen to 4.8% through November.[1] While housing disinflation had stalled somewhat, prices for rent of primary residence and OER recorded their smallest increases since July 2021 and April 2021, respectively.

To be sure, housing is not the only category contributing to core inflation’s stickiness in recent months: inflation for core services excluding housing remains elevated above pre-pandemic levels, and added 1.4 percentage points to yearly core CPI inflation in November. Over the past year, core services ex. housing prices have risen 4.3%, while core goods prices have fallen 0.6%. While core inflation remains on a path to return to the Federal Reserve’s target, with 3.3 percentage points of disinflation since its peak in September 2022, these two trends pose a risk to the inflation outlook. A reversal in the downward trend in core goods prices or stalling disinflation in non-housing services could put upward pressure on core inflation.

Challenges of measuring CPI housing inflation

CPI shelter includes two housing components: rent of primary residence and owners’ equivalent rent (OER). The first component tracks prices paid on both current and new rents, lagging certain market measures, like the Zillow Observed Rent Index, that give greater weight to new rents (Conner et al. 2024). The BLS collects rent data by surveying subsamples of household units at 6-month intervals. It then estimates OER by imputing from its rental survey what owner-occupied units would rent for if they were on the market (BLS 2024). The staggered surveying technique introduces a lag into this component as well. The task of measuring housing inflation is made additionally challenging due to fundamental differences between rental and owner-occupied housing, as well as measurement error from non-responding households.

Housing inflation model

To better understanding housing inflation and its potential path, CEA’s updated housing inflation model incorporates three elements to address these measurement challenges. First, we include lagged housing inflation data as well as past forecast errors to inform current model predictions.[2] We also include two independent variables: the 6-month lag of the Zillow Observed Rent Index is included as a proxy for primary resident rents and the 16-month lag of the Case-Shiller Home Price Index as a proxy for OER.[3] Both variables enter into the model as year-on-year growth rates. These variables, which are heavily associated with market rents and home prices respectively, allow the model to better capture timely changes in housing inflation.

The Model’s Expectations Going Forward

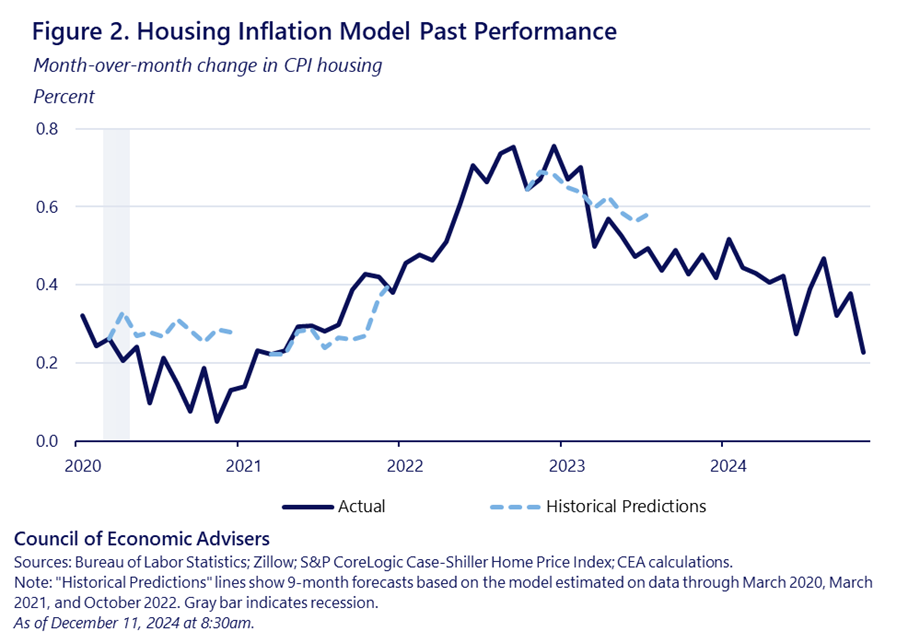

Figure 2 compares the model’s historical predictions to actual housing inflation. As demonstrated by the 9-month ahead forecasts in Figure 2, the model performs well at predicting the late 2021 uptick in housing inflation (based on the model’s prediction as of March 2021) as well as the disinflation beginning in early 2023 (based on the prediction as of October 2022).[4] The model’s prediction for month-over-month housing inflation in November 2024 was 33 basis points, 10 basis points higher than actual housing inflation this month.[5]

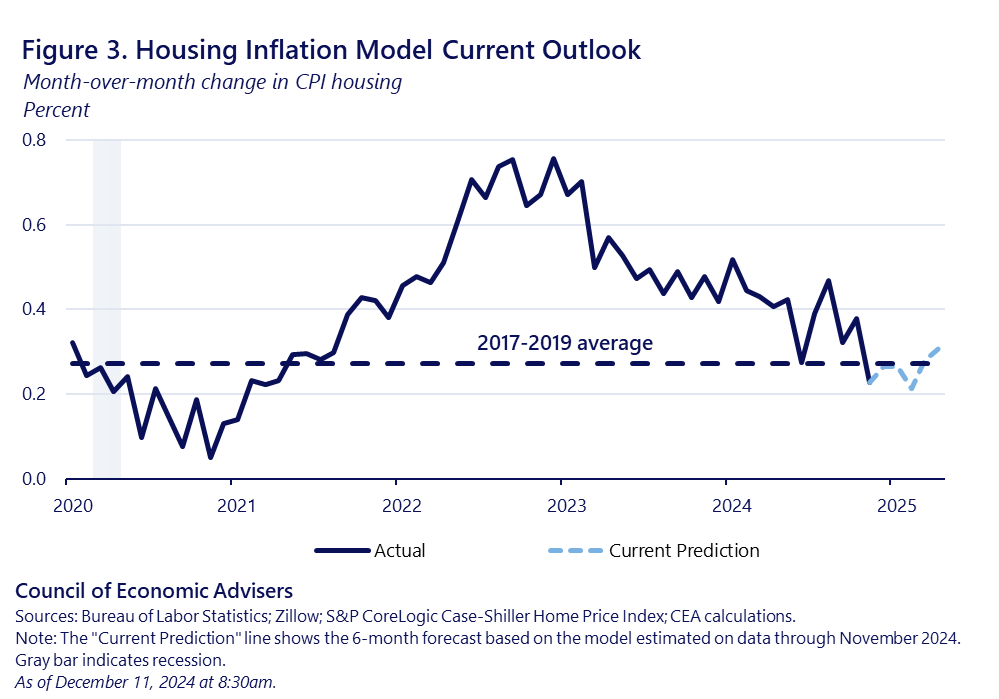

Housing inflation in November declined below the 2017-2019 month-over-month average for the first time since April 2021. The model’s current prediction for housing inflation over the next 6 months, shown by the light blue line in Figure 3, tracks closely with its monthly pre-pandemic average, but this forecast is accompanied by substantial uncertainty. Given the ongoing structural shortage of housing supply and the potential for housing to continue to add price pressures to core inflation, increasing the stock of affordable housing remains critical.

Technical Appendix

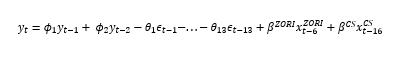

The housing inflation model is a time series model with two autoregressive terms and 13 forecast errors, known as an ARIMA (2,1,13). There are two independent variables: the 6-month lag of the Zillow Owner Rent Index (ZORI), and the 16-month lag of the Case-Shiller Home Price Index (CS). The model can be written as:

Where yt is the single-differenced monthly housing inflation series and Et-1 represent forecast errors. We define housing inflation as the combination of rent of primary residence and owners’ equivalent rent, which together make up about 95% of CPI shelter inflation.

[1] CPI shelter inflation is primarily made up of rent of primary residence and owners’ equivalent rent, which together make up about 95% of shelter inflation. The remaining categories such as lodging away from home (i.e., hotels) are only a small share of shelter inflation.

[2] We select an ARIMA model with 2 autoregressive components and 13 forecast errors, informed by autocorrelation and partial autocorrelation tests. See the Technical Appendix for additional details.

[3] Although housing prices are not an obvious addition, in principle, to predict housing inflation, they are helpful for the model fit as an empirical matter.

[4] We present the model’s forecast miss during the unanticipated shock from COVID-19 to housing inflation, confirming that the model is not overtrained.

[5] When tested on a rolling basis from February 2020 to October 2024, the model misses the next month’s month-over-month housing inflation by 7 basis points on average in absolute terms.