Some Lessons From 47 (!!) Jobs Reports

The November jobs report out this morning is the 47th employment report scrutinized by the CEA since the Biden-Harris Administration took office in January of 2021. It showed that job gains bounced back in November, with employment up by 227,000 and back on track after hurricane and strike activity distorted October’s reading. At 4.2%, the unemployment rate ticked up a tenth but is still low in historical terms, as we show below. Average hourly earnings grew 4% over the past year, continuing to outpace inflation, last seen (in October) at 2.6%. Overall, the job market remains strong, as has been the case for most of the Biden-Harris Administration. For CEA’s take on the November report, see our X thread.

As our tenure winds down—this is our penultimate jobs report!—it seemed like a good time to review some key insights into the U.S. job market over these years. Some are only apparent after the pandemic experience, and some are much older insights, but all are important for thinking about the labor market as we move into 2025.

Persistently strong labor markets are as achievable as they are essential

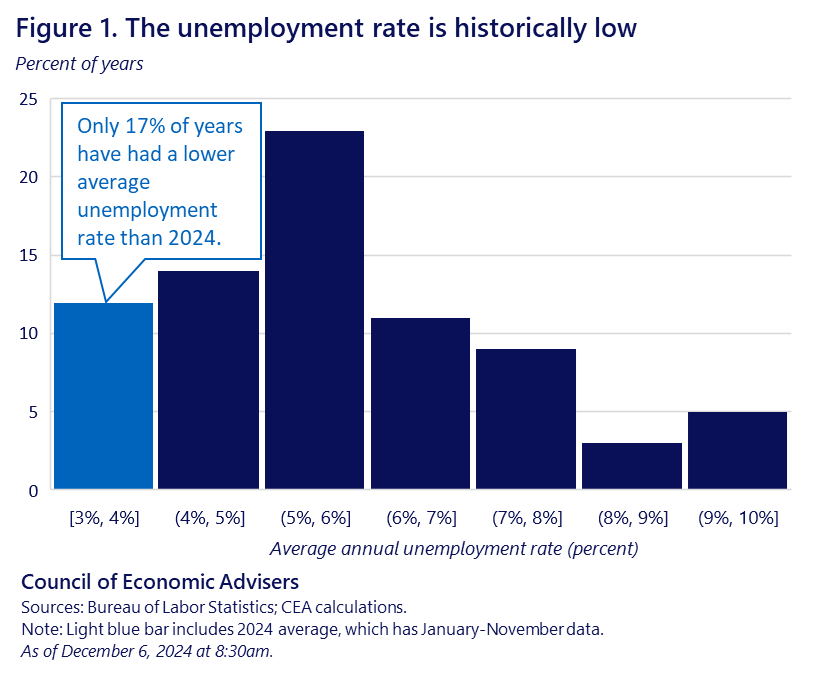

The unemployment rate so far in 2024 falls in the bottom fifth of annual averages over the last 75 years, marking the fourth year of a remarkably strong economic expansion. As CEA has covered before, the unemployment rate has persistently beaten even the rosiest of forecasts over the last few years.

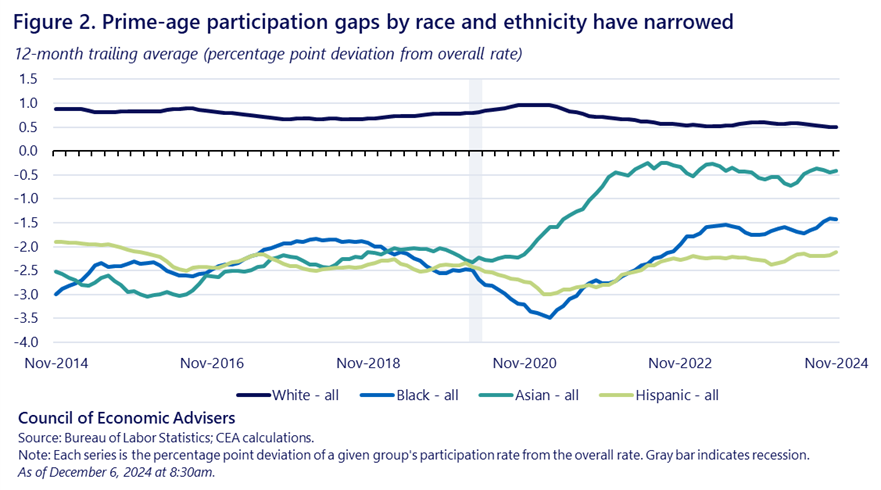

Strong economic growth generates strong labor demand. And strong labor demand, through rising employment and wages, reinforces economic growth. Such a virtuous cycle has helped to keep the unemployment rate low and the economy at full employment, which in turn has helped to lift the labor market’s most vulnerable groups. We dedicated a chapter in the 2024 ERP to this topic, documenting all the ways in which this occurs. In the current economic expansion, this dynamic is evident in compressed labor force participation gaps. See Figure 2.

Persistently full employment, especially when accompanied by labor reallocation to better job matches, may even contribute to faster productivity growth, which has been particularly healthy over the last two years. When the job market stays tight, workers are better able to upgrade their jobs, typically earning more and finding a more productive fit. Also, if firms have to pay workers more because full employment boosts wages, employers can protect their profit margins by discovering efficiency gains.

A hot labor market can normalize without much unemployment increase

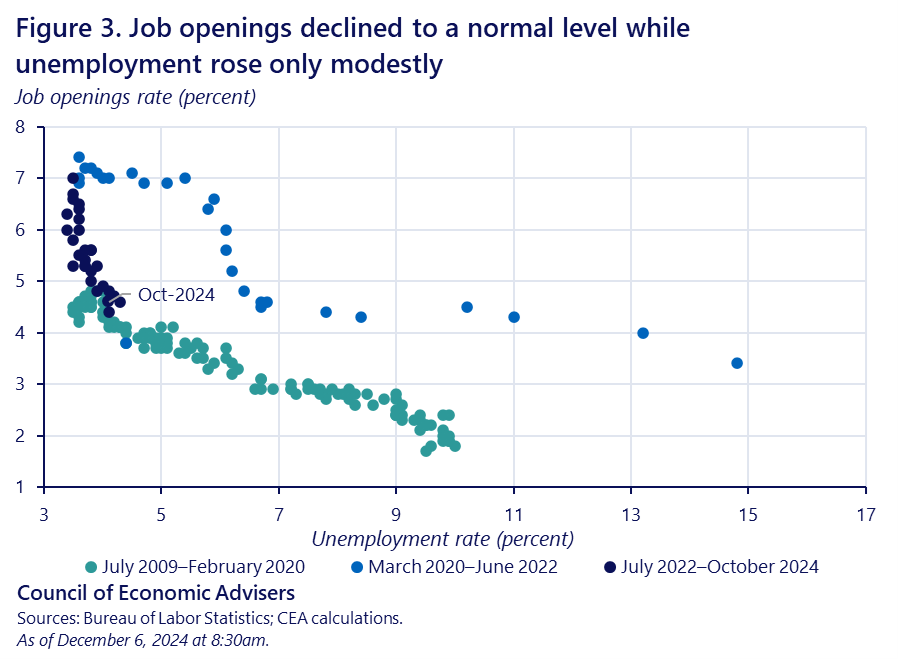

When the labor market becomes overheated—as it did in 2022, with a peak of 2 job openings for every unemployed worker—are all of these gains at risk? Some economists believed that the labor market could only cool to a sustainable level with considerable increase in unemployment, a view that was supported by the historical experience. Relatedly, many believed that both a decrease in job openings and an increase in unemployment were required to tame inflation.

So far, a relatively painless normalization has been achieved, bucking the pattern seen in the past. The ratio of job openings to unemployed is now 1.1, with unemployment still at a modest 4.2%. See Figure 3 for the sharp vertical drop in in job openings, plotted in the standard Beveridge curve diagram.

Part of the reason for this achievement was the unusual nature of the pandemic experience. Inflation was mostly (not wholly) caused by supply shocks rather than the tight labor market, and as supply constraints abated, so did inflation—without an attendant sacrifice of much higher unemployment. At the same time, post-pandemic labor market reallocation, including job-to-job switching, rehiring in service-oriented jobs, and more, was associated with a sharp tightening of the labor market that also eased over time.

The key importance of labor supply

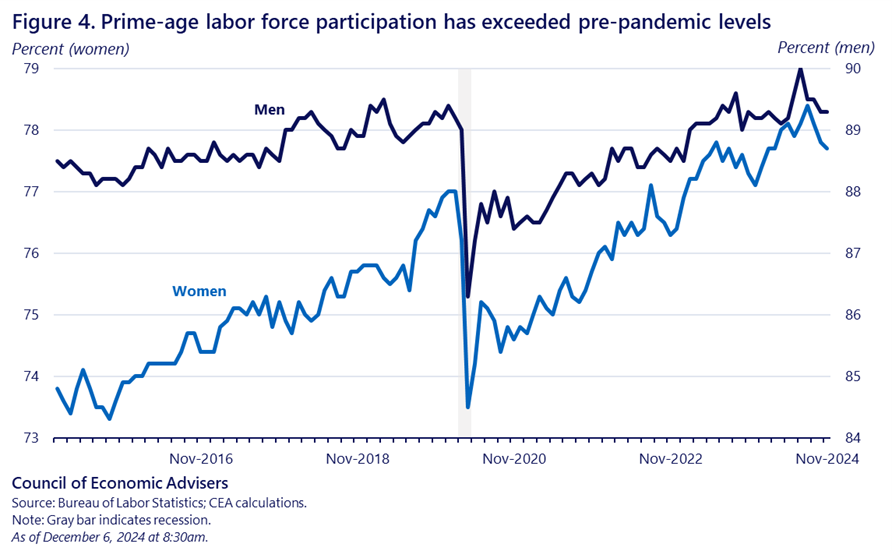

The low unemployment rates shown above are an important piece of a healthy labor market—jobs must be available for those who look for them. But it also matters how many people are available for work. It is not a new insight that high and rising labor supply is a key ingredient of a lastingly strong labor market. However, it took on new relevance in the post-pandemic economy, as supply constraints spurred inflation and hampered recovery.

In this context, it is all the more important that the conditions exist for robust labor force participation. Figure 4 shows the rise in prime-age women and men’s participation over the last several years. In the first years of the pandemic recovery, the Biden-Harris Administration encouraged a rebound in participation with distribution of COVID-19 vaccines and a variety of worker supports, including policies to lower child-care costs; later in the expansion, elevated immigration helped to expand labor supply.

Potential concerns for the healthy labor market

One of our jobs here at CEA is to track risks to the outlook. We do so here in regards to potential threats to the continued strength of the job market. Of course, any number of threats could materialize; below we discuss three that have been part of recent policy discussions.

The importance of international trade

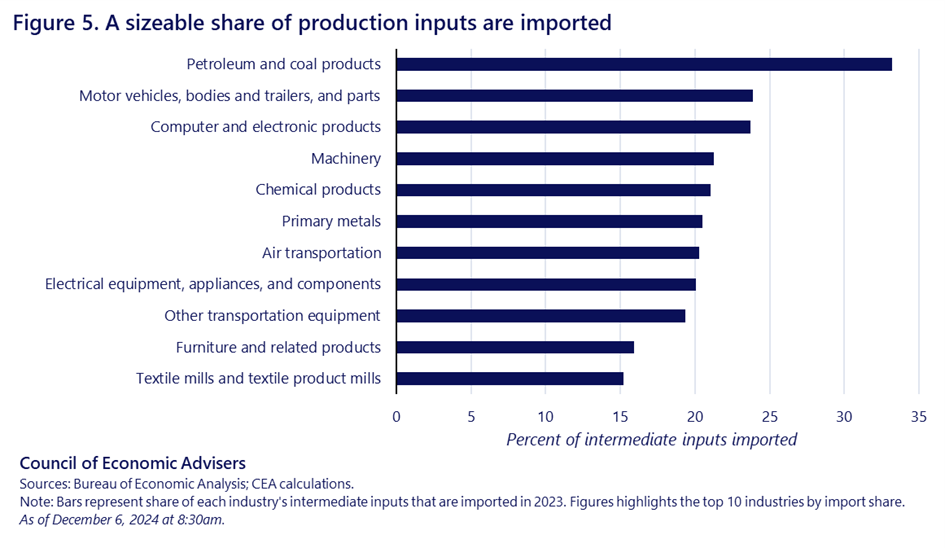

One such threat would come from high and broadly applied taxes on imports: sweeping tariffs, by raising domestic production costs, have the potential to hurt a healthy labor market. Tariffs raise the domestic price of imports, and that in turn raises production costs for the many American producers who rely on imported inputs. Damaging business competitiveness with sweeping (vs. targeted) tariff policy has the potential to disrupt the steady growth and falling inflation that we’ve seen over the last year.

Figure 5 shows the share of intermediate inputs—i.e., goods and services used to produce final goods—that are imported in the 10 U.S. industries with the highest intermediate import shares. Those shares are often quite large, ranging as high as 33%. If the price of these inputs goes up, it will be more costly for firms to produce goods and services for domestic consumption or export. In turn, that could weaken labor demand.

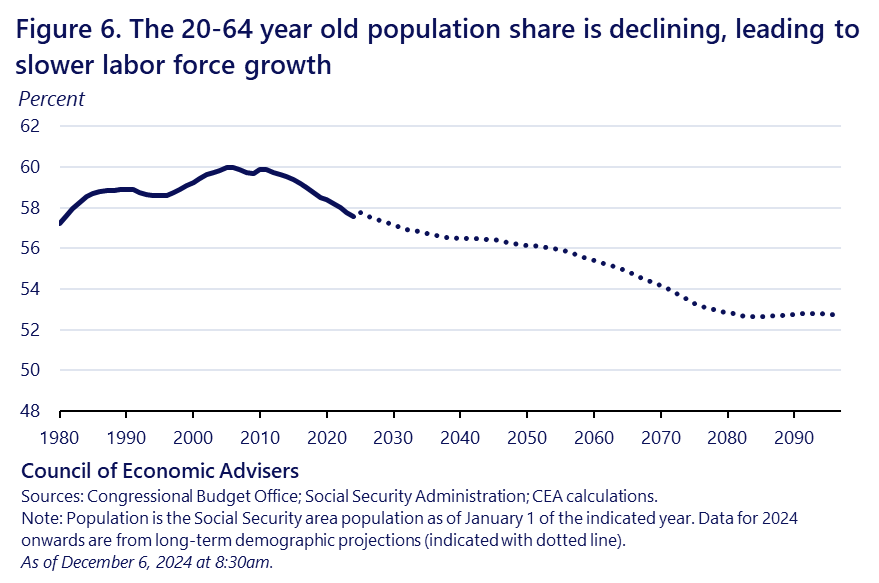

Slowing labor supply growth

The economy faces demographic headwinds in the form of our aging population. As population growth has slowed, the working-age (20 to 64 year old) share of the population—which works at a higher rate than other population segments—has begun to decline and will continue to do so in the years to come. See Figure 6.

Stagnation in prime-age population growth makes it all the more important that labor force participation be supported, as discussed above. It also implies that the U.S. accrues substantial benefits when immigrants legally bring their talents and hard work to the labor market.

Federal Reserve independence

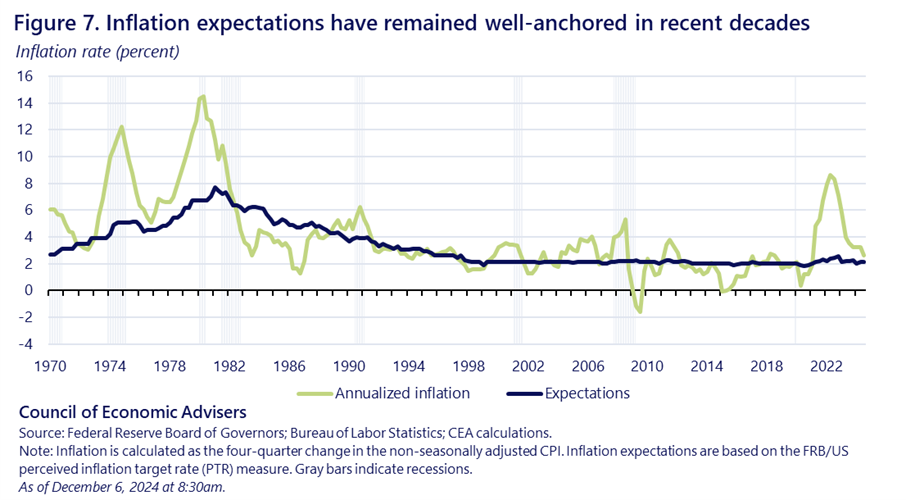

Another way that the healthy labor market could be harmed is by diminishing the ability of monetary policymakers to do their Congressionally mandated job. The Federal Reserve has a dual mandate to achieve stable prices and maximum employment through judicious use of various monetary policy instruments, most notably setting the benchmark interest rate. The work of the Fed is technical and can be challenging in uncertain economic times when the data are sending mixed messages and accurate forecasts are particularly elusive.

The difficulty is multiplied when central bank decisions become subordinated to political considerations. In this situation, many central banks around the world (and the Federal Reserve at earlier moments in its history) have made problematic decisions that spurred persistent inflation that could only be lowered through much higher unemployment. Figure 7 shows how “well-anchored” expectations of inflation remained even in the recent inflationary episode, which is a testament to the credibility established by the Fed’s record of independence.

Perhaps the most important lesson of all is one President Biden has long emphasized: given the opportunity, American workers from all walks of life will deliver the goods (and the services)! The record of the last four years is unequivocal on this point, and the clarion call of a job market characterized by persistently strong labor demand will be met by folks ready and willing to do the work. At the Biden-Harris CEA, it has been our honor to document this progress.