When the Signal Gets Jammed, Look To the Trend

Today’s jobs report is unusually hard to parse because of two distortionary factors that were in play last month. The Southeast was hit with two devastating hurricanes while a strike by Boeing machinists subtracted an unusually large number of jobs from payrolls. CEA often emphasizes the importance of taking any given month’s data with a grain of salt, but these two factors make this month’s report, and especially the low level of payroll employment growth, especially difficult to interpret.

Payroll employment grew by 12,000 last month—well below the prior trend—driven lower by strike and hurricane-related subtractions. Conversely, the unemployment rate, which comes from a different survey that was less affected by strikes and weather, was unchanged at 4.1%. Average earnings grew by 4.0% year-over-year, likely above the rate of inflation. For more on today’s report, check out CEA’s X thread.

Strikes and Weather Significantly Lowered October Payroll Employment

Last week, BLS stated that strike activity, most notably at Boeing, had subtracted about 41,000 from employment gains in October. In fact, employment in transportation equipment manufacturing was down by just about this amount. Other sectors, for example temporary help services (down 49,000), were likely also negatively impacted by the strike.

Last evening, we learned that the leadership of Boeing’s largest union said on Thursday it had agreed with Boeing management on a new contract offer. Should a majority of the union’s members support the new contract—the vote is scheduled for Monday—the strike would end and the striking workers would return to work (and be counted in next month’s payrolls).

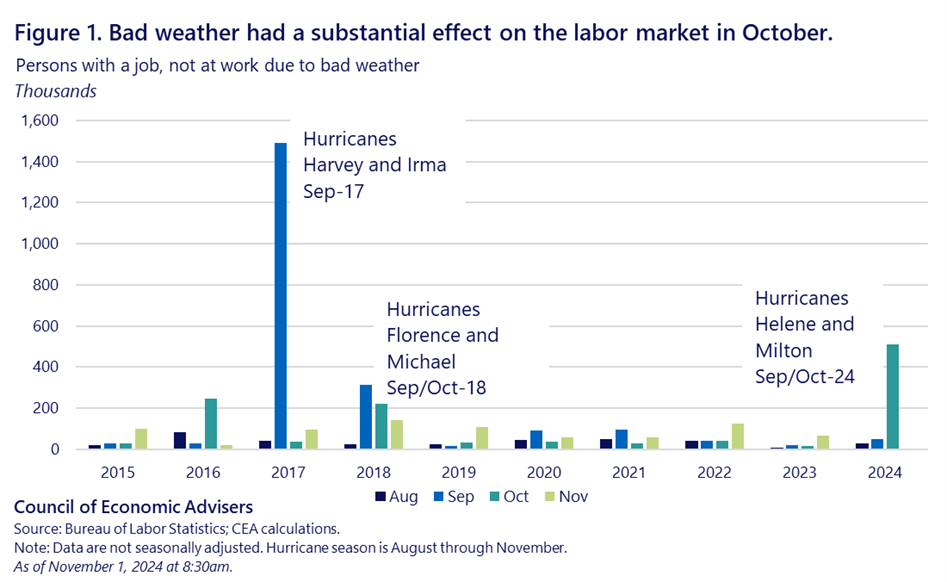

Turning to the hurricane, Figure 1 shows a large spike in the number of employed workers who reported that bad weather kept them from their jobs last month. While BLS is unable to precisely quantify the impact of Hurricanes Helene and Milton on the payroll number, they do note that the hurricanes likely reduced employment growth this month.

Initial claims for unemployment insurance, which quickly rose after the hurricanes arrived, show that the labor market impact of the hurricanes is likely already diminishing. Initial claims have fallen from their recent peak of 260,000 (in the week ending October 5th) to 216,000 in the week ending October 26th.

When the Data Signal Gets Jammed, Look to the Underlying Trend

When our usual signals of the labor market’s condition are jammed by temporary distortions, it is prudent to discount that month’s data and look at the underlying trends in key labor market variables.

Below we take a close look at employment, participation, and earnings growth over the last four years. The story these indicators tell is one of a robust labor market that made a remarkable recovery from the pandemic and continues to offer economic opportunities to the American workforce.

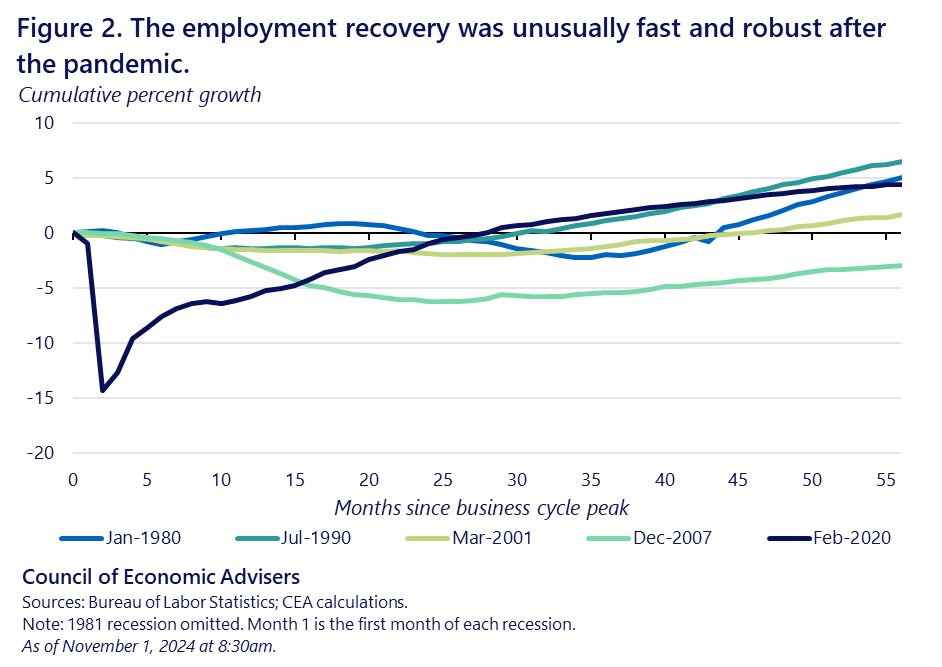

In the wake of the pandemic recession, employment recovered quickly and has continued to grow at a healthy clip. That has not always been the case with prior recessions. Figure 2 shows cumulative growth in payroll employment from the NBER-defined business cycle peak before each recession starting in 1980. By contrast to the prior two recessions, the recovery from the pandemic recession was especially strong. This was the case despite an extraordinary initial loss of employment in 2020 and an aging U.S. population.

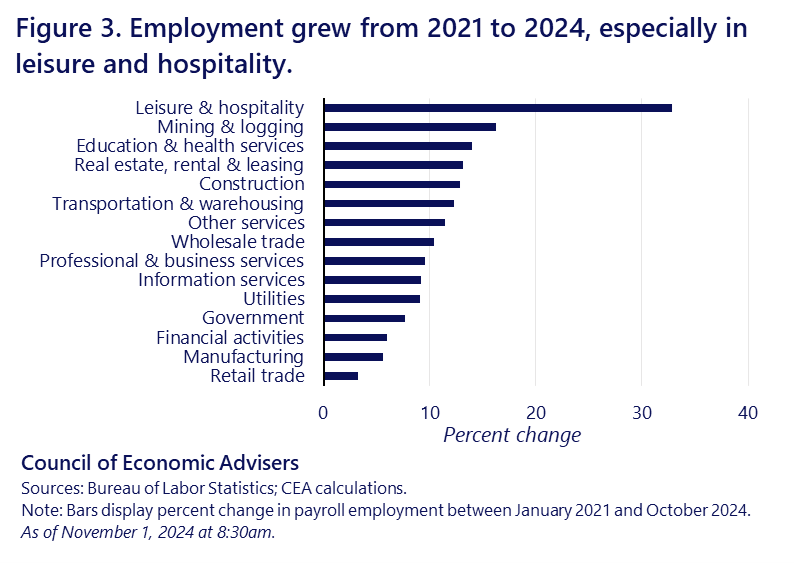

Employment growth after the pandemic recession was unusually strong in leisure and hospitality, which had suffered the largest and most persistent losses in 2020 due to the pandemic’s impact on in-person services. Also experiencing relatively large gains (in percent terms) were mining, education, and construction. But increases since January 2021 were broadly distributed by sector. See Figure 3.

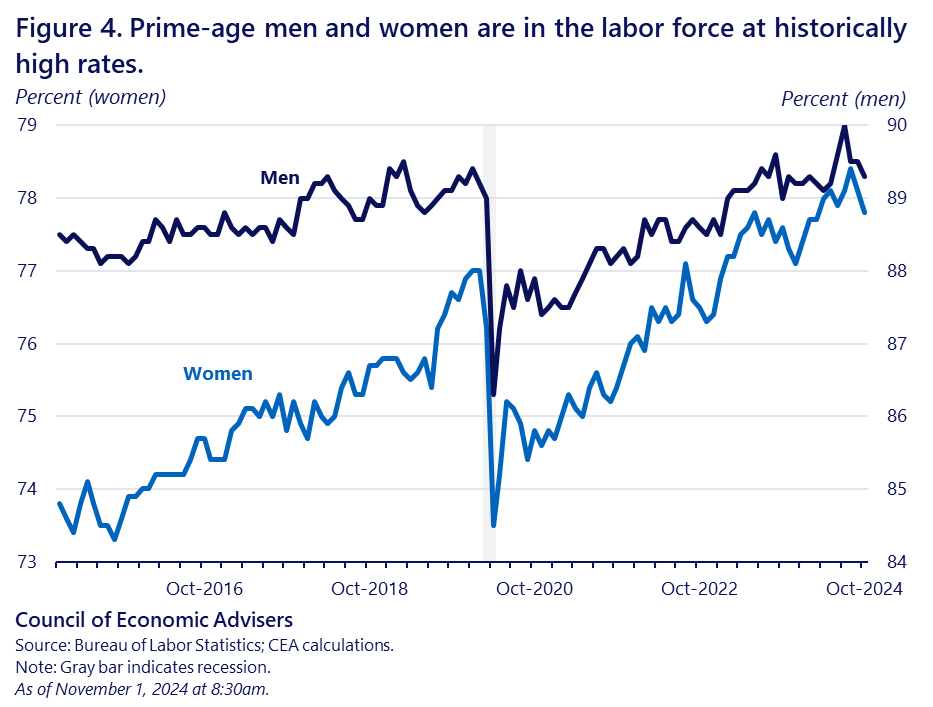

It is often the case that persistently tight labor markets pull in new workers from the sidelines. As such, employment gains in the current labor market expansion have been facilitated by ever-higher rates of labor force participation for prime-age (25-54) men and women (Figure 4). It is especially notable for prime-age men, whose participation has tended to decline over the last 70 years, but is now rising. In a country that is getting older, recent increases in prime-age participation have been a key driver of economic growth.

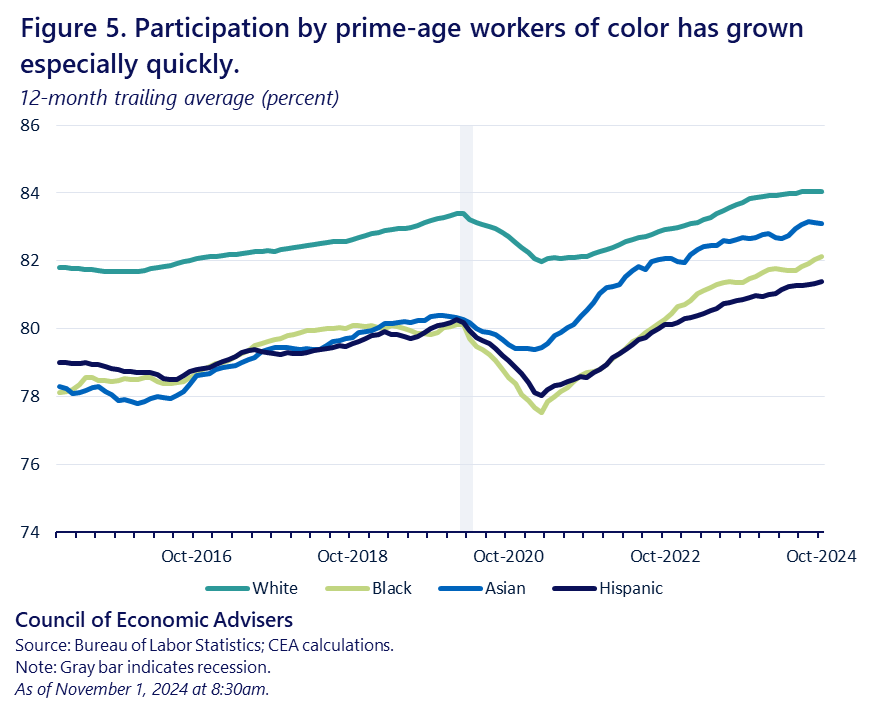

Participation has also risen for prime-aged workers of all races and ethnicities for which the BLS produces estimates. Because periods of full employment are disproportionately helpful to groups most likely to be left behind in slack labor market, gaps in labor force participation have diminished during the current expansion (Figure 5). For example, the gap between Black and white prime-age participation stood at 3.3 percentage points in February 2020 (calculated as a 12-month trailing average). By October 2024, that gap had diminished to 1.9 percentage points.

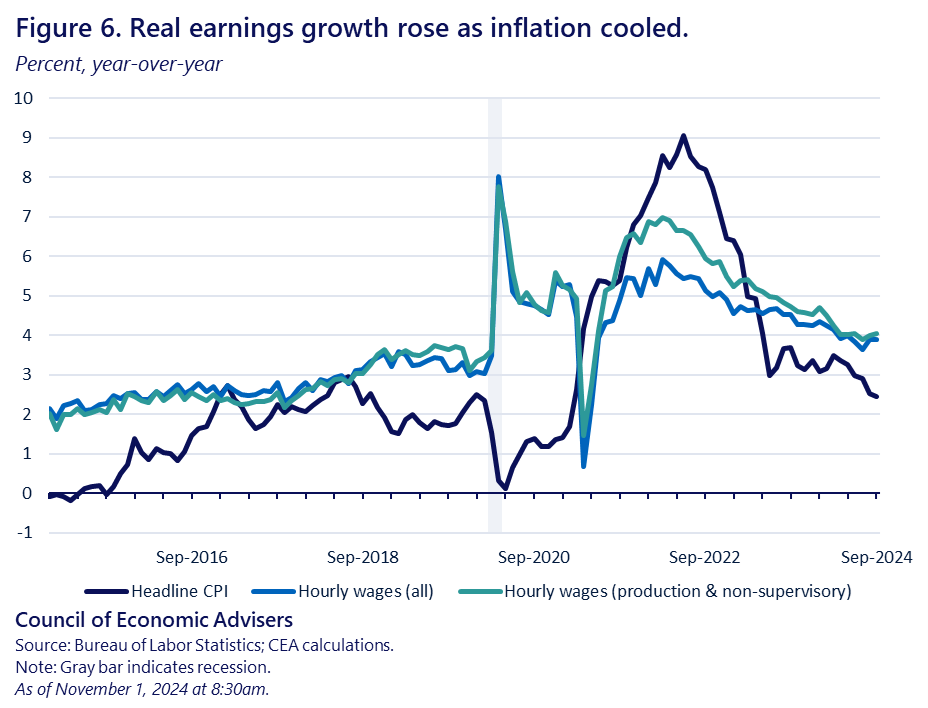

In a particularly important development over this recovery, inflation eased significantly as the job market remained strong, helping to deliver real wage growth. On a year-over-year basis, wage growth has beaten price growth for 17 months in a row, and the gains have been larger for middle- and lower-wage workers. In October, nominal wages were up 0.4 percent, well above last month’s 0.2 percent inflation.

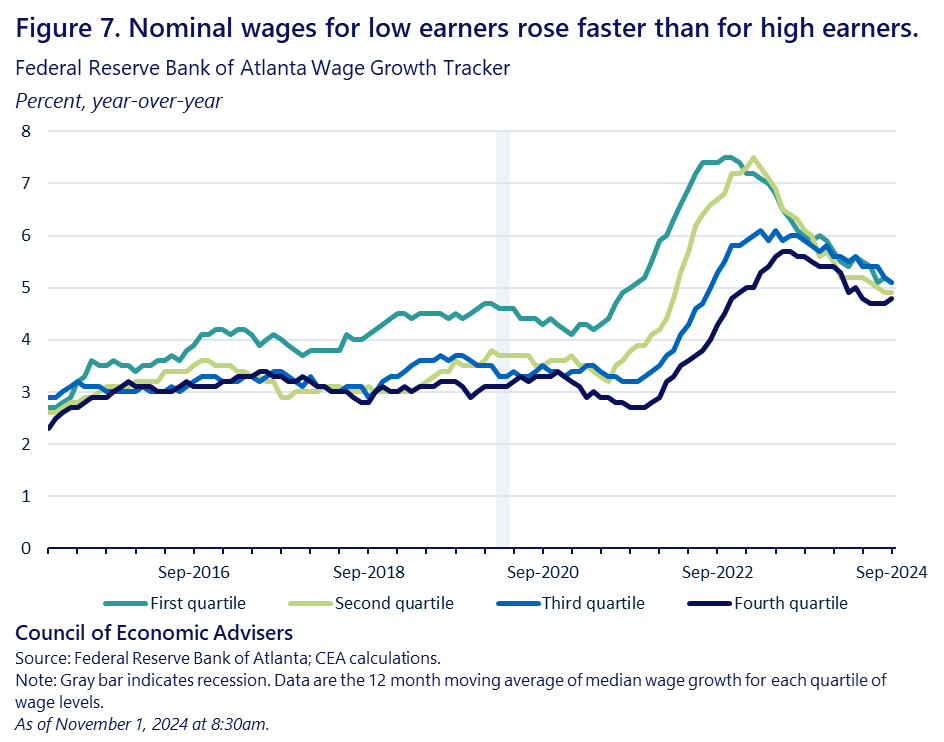

Just as with rising employment, it is important to disaggregate the trend and see the extent to which it is broadly benefiting different groups of workers. Here again, persistent labor market disparities have diminished, as shown in Figure 7. Continuously employed workers in the bottom quartile of wages experienced much stronger nominal wage growth than those at the top. As the labor market normalized in 2024, that advantage has subsided, but the cumulative effect of the last several years has been to substantially reduce long-standing inequality in incomes.

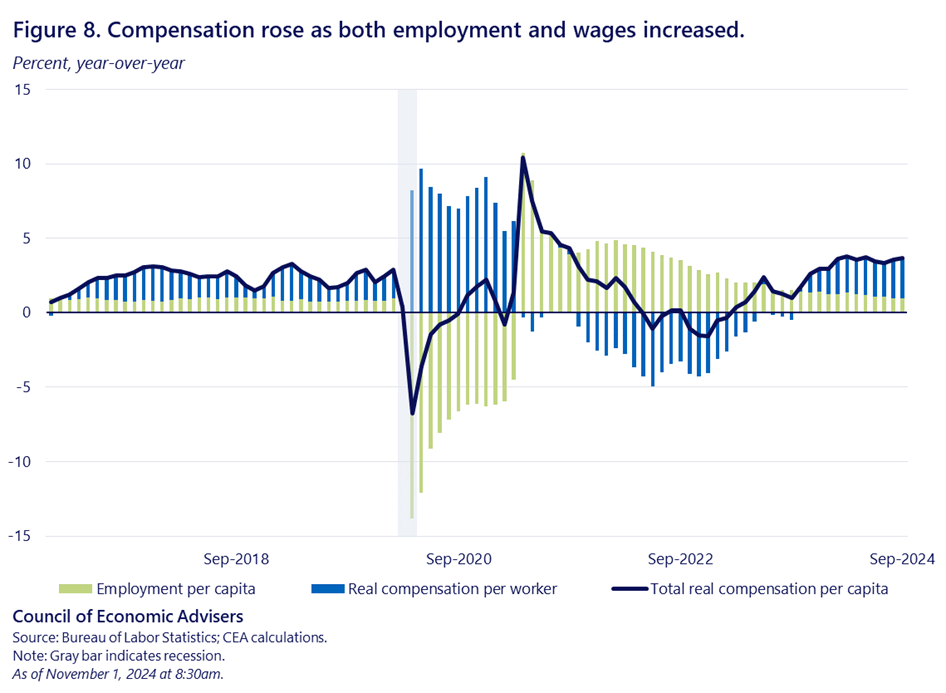

Putting both sides of the labor market together—employment and wages—yields total compensation. Real compensation can rise due to more employment (i.e., more hours of work) at constant real wages, constant hours of work at rising real wages, or some combination of the two. In Figure 8, we decompose real compensation growth into changes in employment and changes in real compensation per employed worker. In 2021 and 2022, job growth (green bars) was a driving factor, partially offsetting falling real compensation. Since then, both rising real wages and job gains (though the latter has slowed as the job market has cooled) have jointly contributed to solid gains in total real compensation.

Although weather and strikes muddied the data for the October jobs report, longer-term trends reveal that the persistently tight U.S. labor market has delivered strong job and wage gains that have been particularly beneficial to middle- and lower-wage workers. Labor force participation has climbed for prime-age workers, and easing inflation has helped to generate consistent real wage gains. Of course, we will continue to work to lower costs for households in key areas, including health care, child care, and housing. But the ongoing strength of the U.S. labor market has been an essential and positive contributor to the current expansion.