Economic Security of Older Women

Women, and women of color in particular, experience persistent workplace inequities throughout their lives, including due to discrimination, occupational segregation, holding jobs with less employer-sponsored benefits, and unpaid caregiving responsibilities. These challenges accumulate over the lifecycle, leading older women to face unique economic challenges.

This note briefly reviews the factors during the lifecycle that may contribute to older women’s worse economic outcomes. We also highlight how these factors disproportionately disadvantage widows, divorced women, and older women of color.

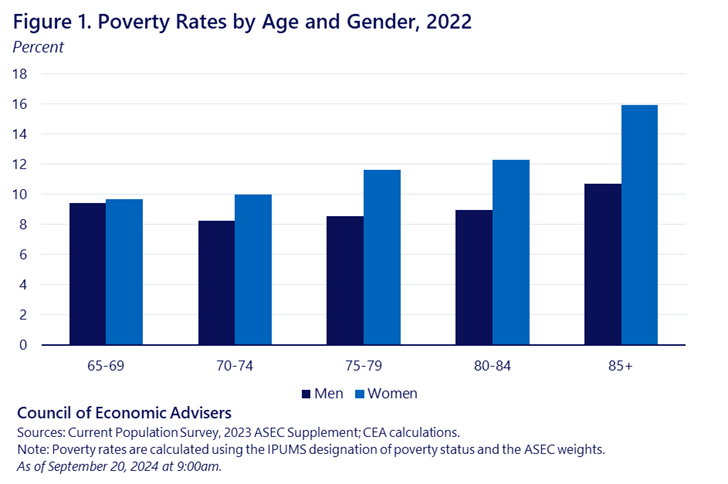

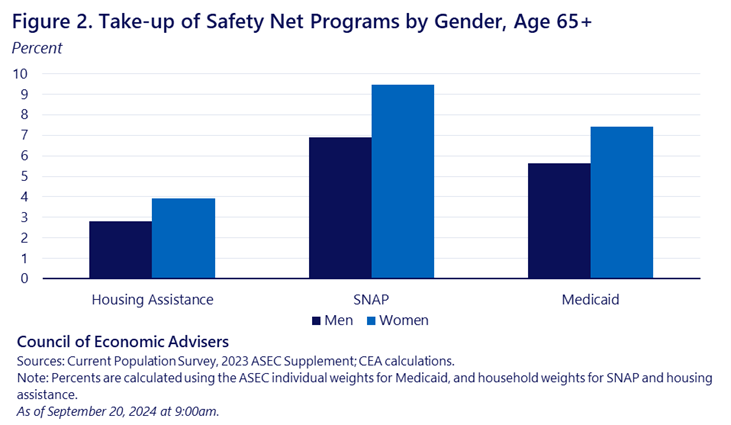

At age 65, women can expect to live around 20 additional years—three years, or 17 percent, longer than men. Also, due to accumulated headwinds women face during their working years, women have lower median lifetime earnings than men and are much more likely to be secondary earners. As a potential consequence of lower earnings, women have lower retirement account balances than men and receive lower Social Security benefits than men. These factors combined contribute to women being much more likely than men to live in poverty at older ages (Figure 1).[1] Specifically, women age 65 and older are 25 percent more likely to live in families with incomes below the poverty line than older men, with differences in poverty rates by gender increasing with age. The practical implication of higher rates of poverty among older women is higher rates of participation in the safety net programs. Women age 65 and older have higher rates of receipt of housing assistance, SNAP, and Medicaid (Figure 2). The higher rates are particularly noteworthy because it signals women are more likely to be disadvantaged given the asset and income test that must be met before an individual can qualify to receive benefits from these programs.

The remainder of this note surveys these challenges and highlights Biden-Harris Administration policies aimed at ensuring that women age with dignity and financial security.

Women have lower wealth at near retirement ages than men

they reach retirement ages, ages 55 to 66. We highlight two of them here.

First, women face challenges in the workplace

During their working years, women face many headwinds. Occupational segregation—the overrepresentation of women and people of color in occupations and industries that pay less, and their underrepresentation in occupations and industries that pay more—and wage and sex discrimination, amongst a myriad of other factors, contribute to the gender-wage gap. One consequence is that women have lower median lifetime earnings and are more likely to be secondary earners than men.

A consequence of the earnings differentials is that because women earn less, they have less money to save for retirement and are eligible for lower Social Security benefits. Research suggests that women have retirement account balances that are about 40 percent lower than men, despite the fact that, conditional on income, women are more likely than men to participate in retirement savings plans. However, because men have higher earnings than women, women’s retirement account balances are lower than men’s. In addition to having lower incomes from which to save, women’s lower earnings lead to lower Social Security benefits than men, on average, as higher lifetime earnings result in higher benefits.

Women of color are likely to face even more hurdles. In addition to sex discrimination, women of color also face racial discrimination. Moreover, Black and Hispanic women are more likely to work in low-wage sectors such as leisure and hospitality, education, and health services. As a result, Black and Hispanic women on average have lower annual earnings than white women, which, over time, results in lower lifetime earnings, contributing to lower Social Security benefit levels as compared to white women. Additionally, Black and Hispanic women have lower levels of wealth than white women. In 2019, single Black and Hispanic women had a median wealth of about $4,000 and about $6,500, respectively, while single white women had a median wealth of about $36,000.

Second, women make up the majority of caregivers

Women disproportionately face a caregiving penalty, and Black and Hispanic women are more likely to be caregivers than white women. Once women reach older ages, they may have had multiple, prolonged caregiving episodes, caring for children, a relative, or a sick spouse. Working less to provide unpaid care can lead to lower levels of accumulated wealth at near retirement ages because women may have fewer dollars to save.

Because women live longer than men, women rely on fewer savings for longer and face higher medical costs

Unfortunately, a consequence of the existing discrepancies in outcomes throughout the lifecycle is that older women have lower retirement savings and receive lower Social Security benefits than men. Women, who tend to live longer, need to rely on these savings longer than men—and need to use these savings to pay for health care costs, which are typically higher for older women than men.

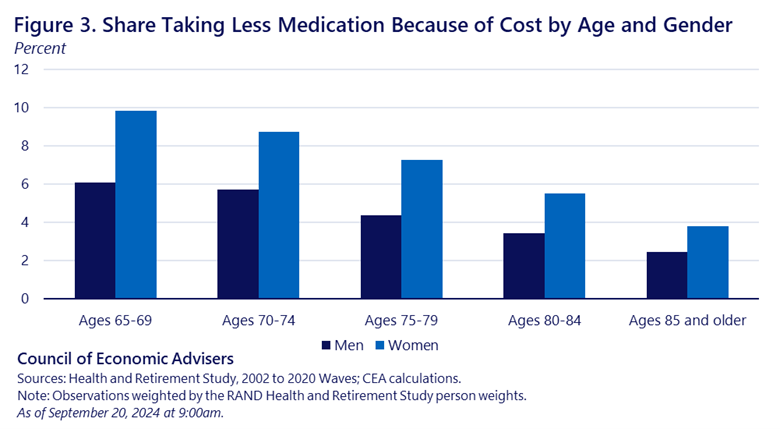

Indeed, CEA analysis shows that women age 65 and older are more likely than men to have reported taking less medication than was prescribed because of the cost. At ages 65 to 69, about 10 percent of women reported taking less medication than prescribed because of cost, while 6 percent of men reported the same; at ages 85 and older the share of women reporting taking less medication than prescribed because of cost declined to about 4 percent, while only 2 percent of men ages 85 and older reported the same (Figure 3).

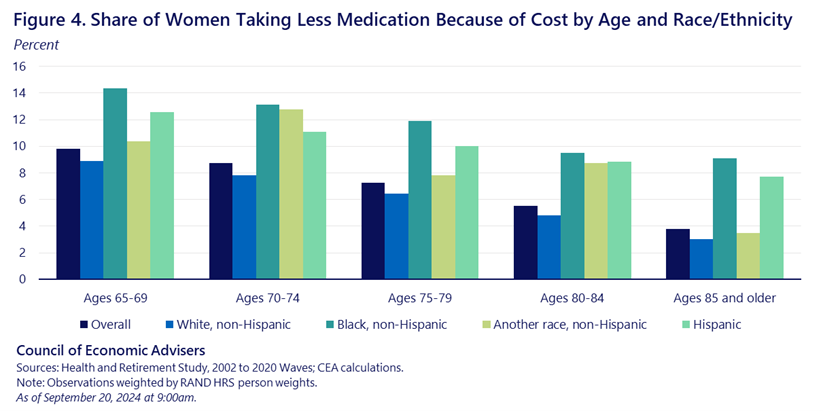

Black and Hispanic women more likely than other women overall to report skipping medication due to costs (Figure 4). At ages 65 to 69, 14 percent of Black women and 13 percent of Hispanic women report skipping medication compared to only 9 percent of white women.

Marital status amplifies these challenges

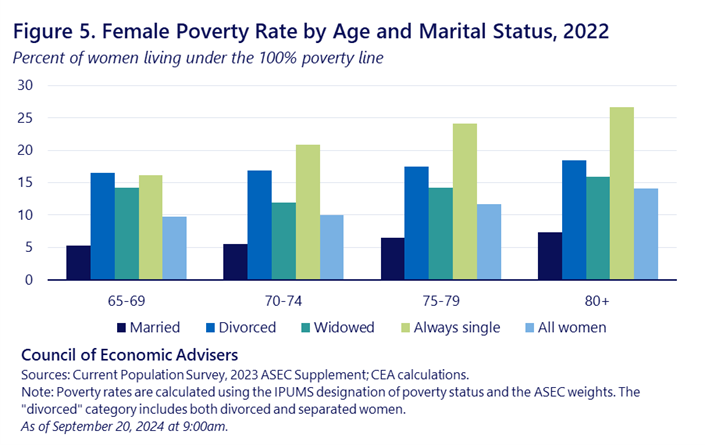

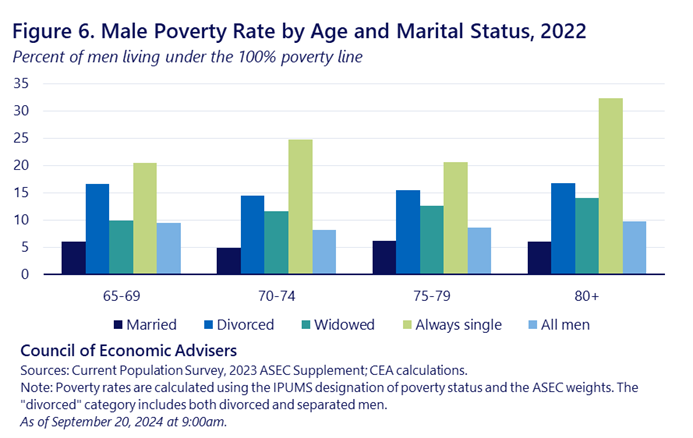

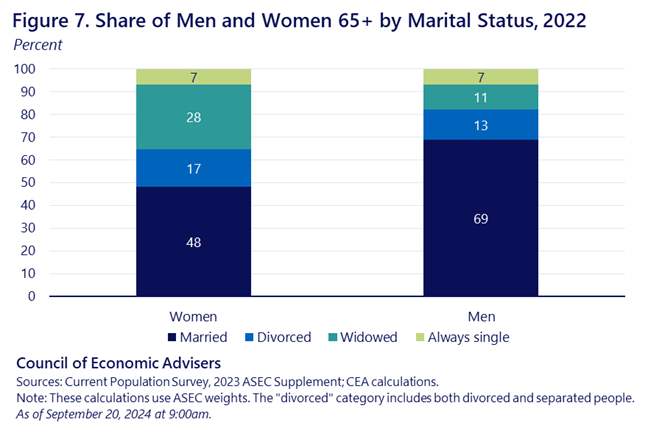

Marital status and changes, such as divorce and widowhood, can have a significant impact on the economic and financial security of older women. The poverty rate increases with age for women over age 65, but remains relatively flat for men (Figures 5 and 6). This is due in part to the fact that women are more likely to be widowed and divorced than men at ages 65 and older (Figure 7).

While men and women are both negatively affected by widowhood, they are not impacted in the same way. The disruption to women appears to be primarily financial, while for men, the disruption appears to be primarily mental health related. In addition, for women, widowhood has been found to be associated with lower wealth holdings, which could lead to lower incomes because there are less resources to draw from.

Similar to the negative effects associated with widowhood, older women are also much more likely to be negatively affected by divorce than older men. Research suggests that women who divorce at ages 50 and older experience a decline of about 45 percent in their standard of living, as measured by their income-to-poverty ratio; men experience a decline of about 21 percent in their standard of living. Moreover, to the extent that re-marriage offsets some of the negative effects associated with divorce, older women are less likely to remarry than older men. Only about 20 percent of older women remarried or re-partnered following a divorce, whereas 37 percent of men do. If marriage provides a buffer against the headwinds women face earlier in life, the lower rates of re-partnering suggest women may be more likely to face the negative effects associated with divorce for longer periods.

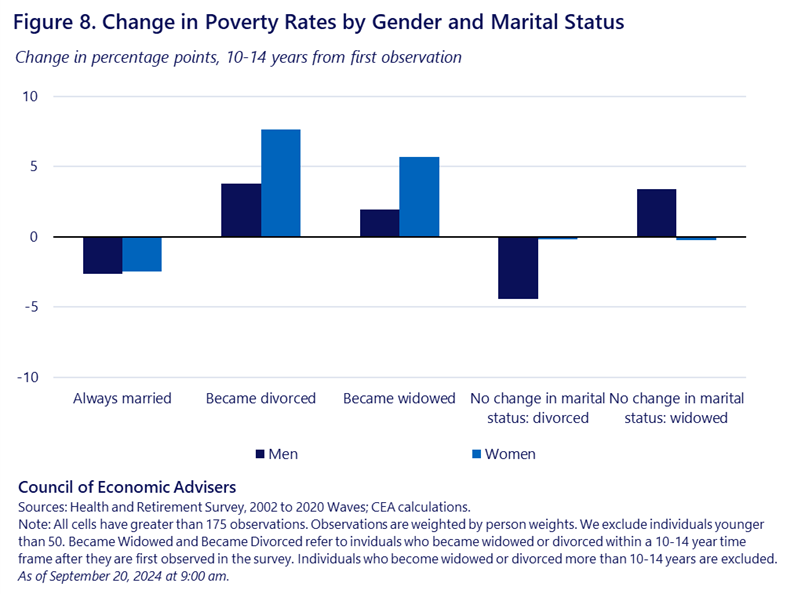

To illustrate the impact of changes in marital status, CEA calculated the change in poverty rates for older men and women by whether or not they were always married, became divorced after age 50, became widowed after age 50, or had no change in marital status (Figure 8).[2] For older men and women who were always married at older ages, their poverty rate falls as they age. However, becoming widowed or divorced after age 50 is associated with higher poverty rates for women, with a much smaller effect for men.

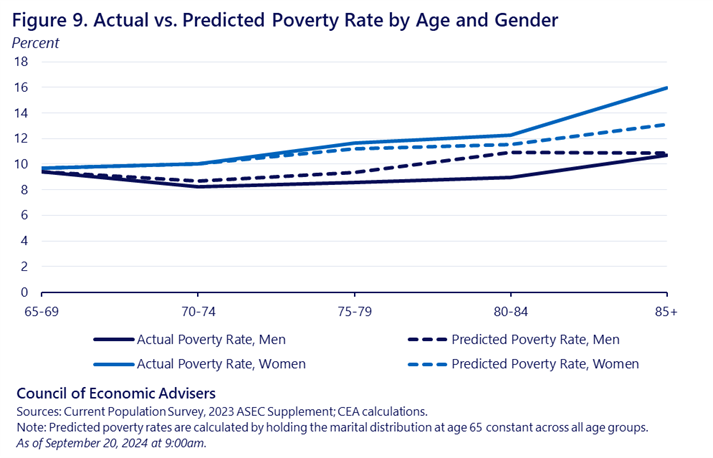

CEA also calculated what the poverty rates for all older women and all older men would have been if there were no changes in marital status between ages 65 to 69 and older ages (Figure 9).[3] For women, the overall poverty rate would be lower at every age from ages 75 to 79 and onward. For men, the overall poverty rate at every age older than ages 65 to 69 would be higher.

These findings suggest the importance of changes in the marital status for the likelihood of being in poverty. Both divorce and widowhood lead to large negative effects for women, potentially signaling the importance of the marriage for older women. Because women are more likely to earn less during their working years and have lower savings than men, marriage may allow women to offset lower earnings and savings by pooling resources. When the marriage ends, either through divorce or the death of the spouse, much of the economic security provided by marriage is lost and women, potentially because they have faced economic headwinds earlier in their lives, may be more likely to experience adverse economic outcomes.

Policy Solutions

Differences in poverty at older ages between men and women may reflect the accumulated headwinds women face during their working years. The negative economic outcomes of older women highlight the importance of addressing the economic headwinds women face throughout the lifecycle.

To address these headwinds, the Administration has implemented policies that work to close the gender and racial wage gaps, ensure all people have a fair and equal opportunity to participate in the labor force, and support their families.

The Biden-Harris Administration has focused on ways to lower child care costs for families. The ARP Child Care Stabilization program delivered support to over 225,000 child care programs serving as many as 10 million children across the country. Over 90 percent of the child care programs that have received assistance are women-owned. Earlier CEA analysis found that this stabilization funding supported savings for families with young children, raised the real wages of child care workers, and helped hundreds of thousands of women with young children enter or re-enter the workforce. In addition, in April 2023, President Biden signed an Executive Order with more than 50 directives to increase access to affordable, high-quality care and boost job quality for early educators and long-term care workers, who are disproportionately women of color.

To reduce the penalties women face as a result of their role as caregivers, the Administration has championed efforts to increase compensation and improve job quality for caregivers, expand access to affordable, high quality long-term care, and prioritized making child care accessible and affordable for more families. Research shows that increased access to care increases the labor force participation of women. These policies can help reduce the economic disparities at older ages for future generations.

The Administration is also focused on ensuring equal access and pathways to high-quality jobs for all Americans. The Administration has taken steps – such as the launch of the Good Jobs Initiative – to ensure increased access to these jobs, including for women, people of color, and members of other communities currently underrepresented in these growing sectors. And in a continued effort to correct earnings and employment disparities at working age, earlier this month, the President signed a new Executive Order on Investing in America and Investing in American Workers, which will help ensure that the Biden-Harris Investing in America agenda continues to promote good, high-quality jobs with paths to the middle class. The Executive Order promotes strong labor standards such as family-sustaining wages, workplace safety, and the free and fair opportunity to join a union, and encourages agencies to implement these standards through their Investing in America programs. In addition, the Administration is focused on closing gender and racial wage gaps, including through the Administration’s work to eliminate discriminatory pay practices in the Federal government and Federal contracting workforces.

And the Administration is committed to ensuring equality for women in the workplace. The President signed into law the bipartisan the Pregnant Workers Fairness Act and the PUMP for Nursing Mothers Act to provide accommodations to pregnant and postpartum workers.

While the cost of healthcare is an issue for all older persons, it may be particularly challenging for older women. To ensure everyone can afford their medication, the Biden-Harris Administration has prioritized lowering prescription drug costs. The Administration oversaw the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, which included several provisions to reduce out-of-pocket prescription drug spending by Medicare beneficiaries. One of the most notable provisions was the provision to negotiate drug prices, which resulted in the August 2024 announcement that the Administration had successfully negotiated lower prices for 10 drugs, saving millions of seniors and other Medicare beneficiaries $1.5 billion in out-of-pocket prescription drug expenses.

From addressing workplace inequity to increasing access to care to lowering health care costs, the Biden-Harris Administration is committed to delivering the support women need to age with financial security.

[1] In this note, we use the Official Poverty Measure when measuring poverty.

[2] For this analysis, we require that we observe an individual at younger and older ages. Individuals who die or otherwise exit the Health and Retirement Study sample are excluded. We include individuals when we first observe them at ages 50 or older. An individual can only be in the sample once. We also exclude any individuals who do not fit into the six categories, likely because they had multiple marital status changes. We exclude individuals who remarried after 50 and who never married because of sample size limitations. The change in poverty rates is calculated as the difference between the poverty rate of the group (e.g., always married women) at younger ages and the poverty rate of the group at older ages, where the same individuals are in both the younger and older groups.

[3] Specifically, we determine the share of men and women who are married, never married, divorced, or widowed at ages 65 to 69 and then multiply the observed poverty rate for each marital status at every older age and then sum the resulting products across marital status.