Beating the Forecasts: How the US Economy Defied Expectations

Last week we learned that yearly inflation, as measured by the Consumer Price Index, was 2.5 percent, close to its pre-pandemic rates. While this result is largely in line with where economists expected inflation to be by now, most believed it would take a significant increase in unemployment and slowdown of growth to get there. But that was far from the reality of the outcomes. This widespread forecasting error is not simply an academic debate; it means millions of workers and their families have not had to experience the pain of unemployment and recession in order to get inflation back down.

The fact that inflation’s roundtrip has so far occurred without the accompaniment of negative outcomes is one of the most important developments of the current expansion. Moreover, this outcome was not a forgone conclusion: it is, in part, the result of policy choices by the Biden-Harris Administration to shore up American households’ balance sheets, encourage investment in our economy, resolve supply chain disruptions, and support the independence of the Federal Reserve as they fought to keep inflation expectations firmly anchored and inflation in check.

Inflation Forecasts Were Right; Unemployment and Growth Defied Expectations

As CEA has long discussed, inflation picked up in the recovery from the pandemic-induced recession, as strong demand collided with weak supply amidst the snarling of supply chains and unexpected food and energy price shocks caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The consensus during this period among a wide range of experts was that it would take a period of substantially elevated unemployment and tepid growth to bring inflation back under control.

The following analysis shows how that consensus has been wrong, by focusing on the performance of the U.S. economy relative to forecasts made after inflation’s peak in June 2022, as disinflation started to take hold. In keeping with President Biden’s commitment to full employment, rather than sacrificing gains in employment by dis-inflating “on the backs of working people,”[1] the U.S. economy achieved rapid and broad-based disinflation during a period of historically low unemployment – with the lowest unemployment rate of any Administration in 50 years – and strong, above-trend growth. Rather than accepting a sharp increase in unemployment as the necessary solution to contain inflation, the Biden-Harris Administration acted swiftly, working with the private sector to unsnarl supply chains and address commodity price spikes, including by creating the Supply Chain Disruptions Task Force, legislating shipping-rate reforms, and activating the Strategic Petroleum Reserve. All the while, the Administration recognized the independence of the Federal Reserve, whose autonomy is crucial to long-term price stability. This commitment to disinflation without soaring unemployment helped to keep millions of Americans in their jobs over the past two years.

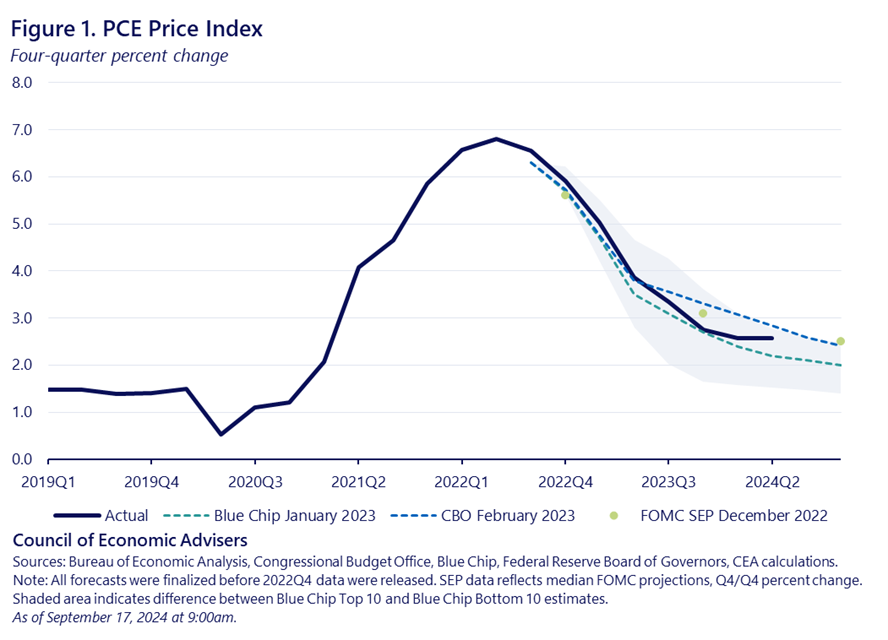

Figure 1 shows that inflation in 2023 and 2024 has evolved closely in line with forecasts made around the end of 2022. In the second quarter of 2024, year-over-year headline PCE inflation was 2.6 percent, close to the FOMC’s December 2022 forecast of 2.5 percent for the final quarter of 2024, below the CBO’s projection of 2.8 percent, and above the Blue Chip Consensus Forecast of 2.2 percent for this quarter.[2]

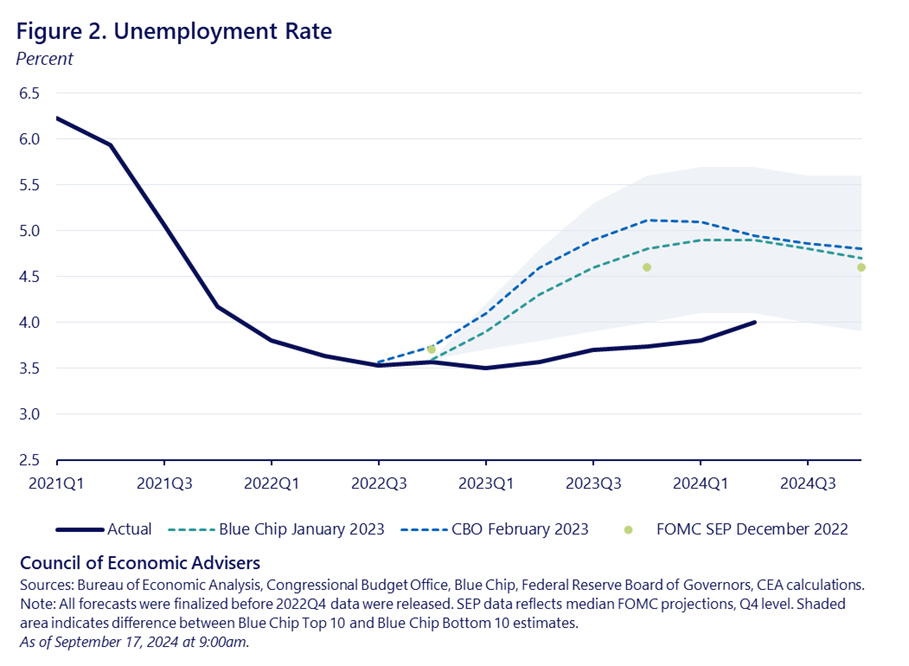

To achieve the inflation paths in Figure 1, most forecasters assumed that unemployment would rise significantly and growth would remain below trend. In fact, while actual inflation is in line with predicted inflation, there are remarkable differences between forecasted and actual outcomes for unemployment and economic growth, which outperformed even the most optimistic Blue Chip forecasts.[3] To be sure, these forecasts are consistent with the widely accepted notion that there is a trade-off between unemployment and inflation, captured by the Phillips curve. While this relationship has held historically, it is not stable over time and has been shown to play out differently under “pandemic economics,” or, more precisely, in the presence of historically large and unusual shocks to the economy’s supply-side.

As Figure 2 shows, unemployment in the second quarter of 2024 is around 1 percentage point below the CBO’s projection and the Blue Chip Consensus Forecast, and below even the average of the 10 most optimistic Blue Chip forecasters. Moreover, unemployment has remained below these projections for the entire forecast horizon.

Real Impact for Americans

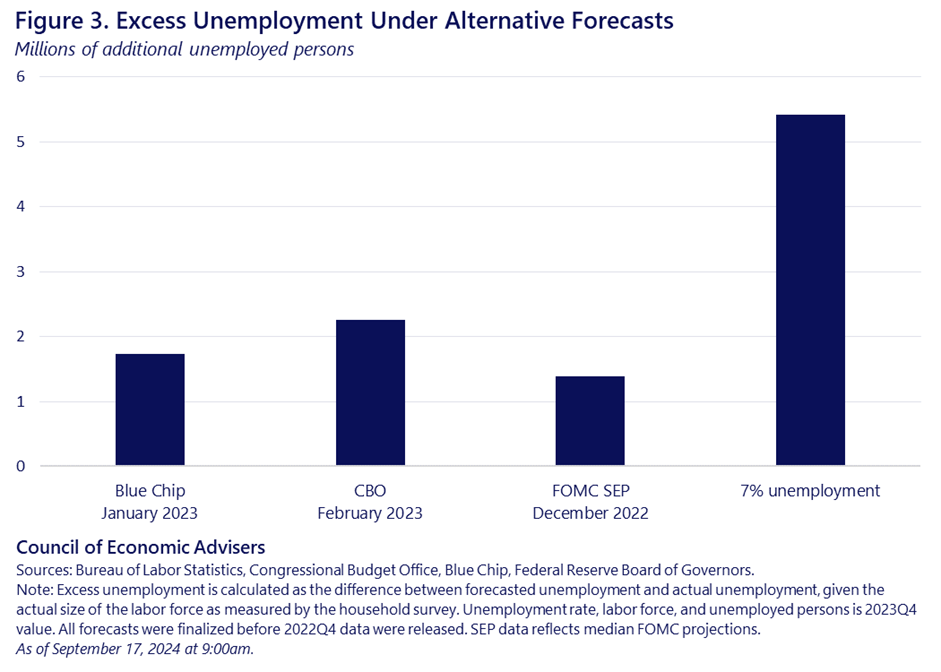

Outperforming forecasts is not about bragging rights; it’s about real lives of working families. Figure 3 displays the millions of additional Americans that would have been without a job under these alternative forecasts. Under the Blue Chip Consensus Forecast, 1.7 million additional Americans would have been out of work at the end of 2023, while the CBO’s projection translates to 2.3 million additional unemployed workers. Forecasts from leading academics indicated that unemployment would need to rise even more than the most pessimistic Blue Chip forecasts, up to 7.5 percent – and stay there for two years – in order to bring inflation back to pre-pandemic levels. This is equivalent to more than 6 million additional Americans out of work. In addition to the immediate pain of job loss, extended periods of unemployment have lasting, scarring effects on families and the broader economy.[4]

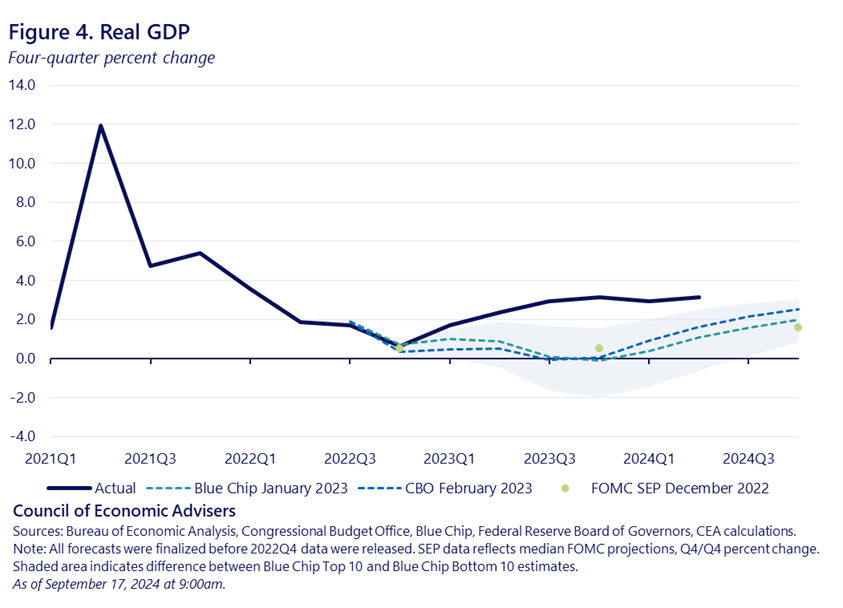

This period of falling inflation without a significant rise in unemployment translated to gains in real wages and incomes that were felt by American workers. In the final quarter of 2023, actual real disposable personal income per capita was about $1,100 higher than would have been consistent with the Blue Chip Consensus Forecast. These gains have kept consumer spending strong and supported real GDP growth. Along with employment and incomes, real GDP growth defied expectations. As shown in Figure 4, real GDP growth has exceeded 2.5 percent for the past year, and it has outpaced the average of the 10 most optimistic Blue Chip forecasts over the entire forecast horizon. Between the final quarter of 2022 and the second quarter of 2024, the cumulative increase in real GDP was 4.3 percent, well above the 1.2 percent increase predicted by the CBO and the 0.7 percent increase predicted by the Blue Chip Consensus Forecast.

Conclusion

Yogi Berra famously said, “It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.” We agree, and forecasting is especially challenging in the context of unusually large and global shocks. In that regard, our point here is not to impugn forecasters but to highlight how, during this rapid disinflationary period, the U.S. economy has maintained its strength. By maintaining a commitment to reducing inflation without accepting large increases in unemployment as a given, families and businesses avoided the persistent scarring effects of unemployment and recession. Furthermore, the combination of falling inflation amidst low unemployment creates a powerful dynamic in which real wages and incomes are growing, and more workers are able to reap these rewards. These outcomes are crucially important for families’ economic well-being. As economic scholars, including ourselves, continue to absorb the lessons of this consequential economic period, this one stands out so far as particularly positive.

[1] The trade-off between rising unemployment and falling inflation is captured by the “sacrifice ratio”, defined as the excess unemployment required to achieve a 1 percentage point reduction in inflation. For example, a sacrifice ratio of 2, within the range of empirical estimates, implies that a 4 percentage point reduction in inflation would necessitate a 4 percentage point increase in the unemployment rate above its natural rate for 2 years, or an 8 percentage point increase for one year.

[2] The FOMC’s Summary of Economic Projections was released on December 14, 2022. The CBO’s February 2023 forecast is based on data through December 6, 2022. The Blue Chip forecast is from January 2023.

[3] Blue Chip Economic Indicators are forecasts from leading economists employed by large U.S. banks, insurance companies, brokerage firms, and manufacturers. Figures 1, 2, and 4 display the consensus forecast as well as the average of the top 10 and bottom 10 forecasts.

[4] See Chapter 1 of the 2024 Economic Report of the President for more details on the persistently negative effects of extended periods of unemployment.