When the Men Buck the Trend: Recent Advances in Men’s LFPR

Payrolls rose 114,000 last month and the unemployment rate rose from 4.1% to 4.3%. This was more labor-market cooling than was expected, but monthly data can be jumpy and there were some weather effects in the July report. Smoothing out some of the monthly noise, the average payroll gain over the past three months was still a healthy 170,000.

For more details on today’s report, see CEA’s X thread.

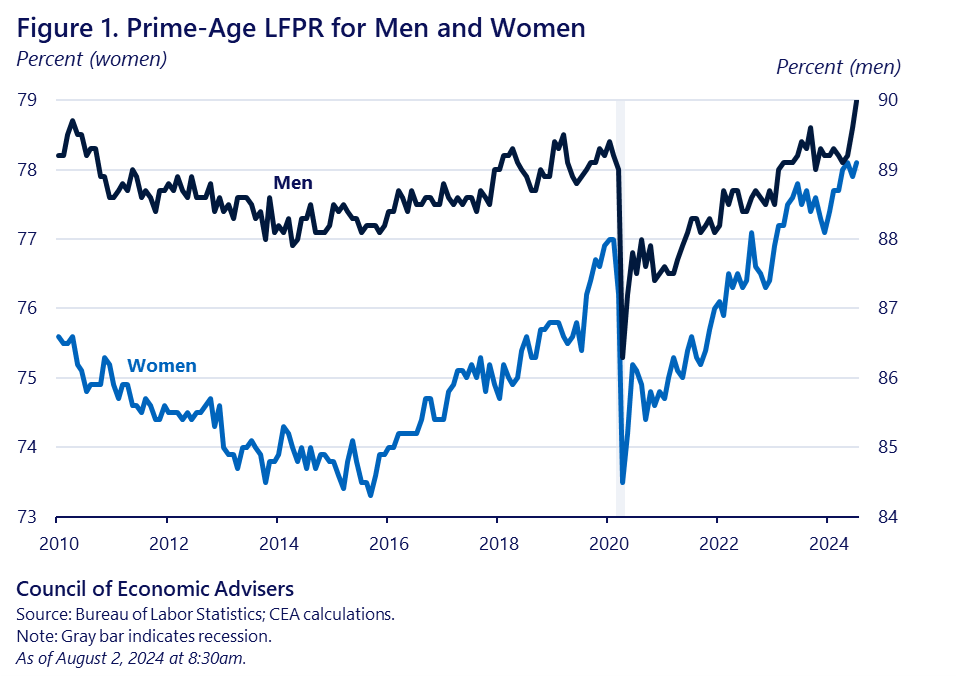

Labor force participation rate (LFPR) ticked up overall, by 0.1 percentage point to 62.7%, but the LFPR for prime-age (25-54) workers saw a solid pop last month, up 0.3 percentage point (ppt) to 84.0%, a 23-year high. Prime-age men’s LFPR rose 0.4 ppt to 90.0% (highest since 2009) and women’s was up 0.2 ppt to 78.1% (tied for an all-time series high). The positive LFPR trend for both groups over the current labor-market recovery is evident in the figure below.

CEA and others have highlighted the increase in women’s labor force participation, as women have been a key driver of the labor market recovery since the pandemic recession.

Less attention has been paid to the recovery in prime-age men’s labor force participation. In fact, it is important to elevate this trend, as it stands in stark contrast to the longer-run decline in prime-age men’s participation over many decades.[1]

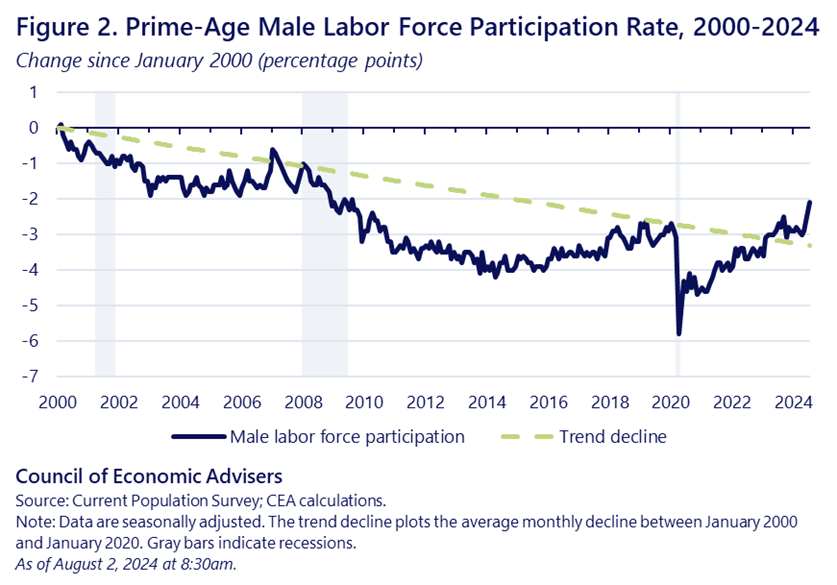

That downward trend is evident in figure 2, which plots the percentage point change in men’s LFPR (relative to January 2000) along with a trend drawn from January 2000 through January 2020. That trend entailed a reduction of 0.01 percentage points each year, bringing men’s LFPR down to 89.4% in January 2020.

But the sharp recovery after the Pandemic Recession has brought prime-age men’s LFPR above its pre-pandemic level and well above its pre-pandemic trend. This is especially notable given that the late 2010s and the post-pandemic periods can be considered roughly similar in terms of how tight the labor market was. Moreover, this recent positive trend appears to be durable; it’s over 4 years old.

Which factors might be supporting prime-age men’s participation? Just as with women, one key factor is the rising educational attainment of prime-aged men. CEA examined this factor separately for men and women, calculating how much of the participation increase—from before the pandemic to today—is associated with educational upgrading. For prime-age women, 0.7 percentage points out of a total increase of 2.1 percentage points were associated with rising educational attainment. For men, all of a 0.3 percentage point increase can be accounted for in the same way.[2]

How LFPR has powered men’s employment

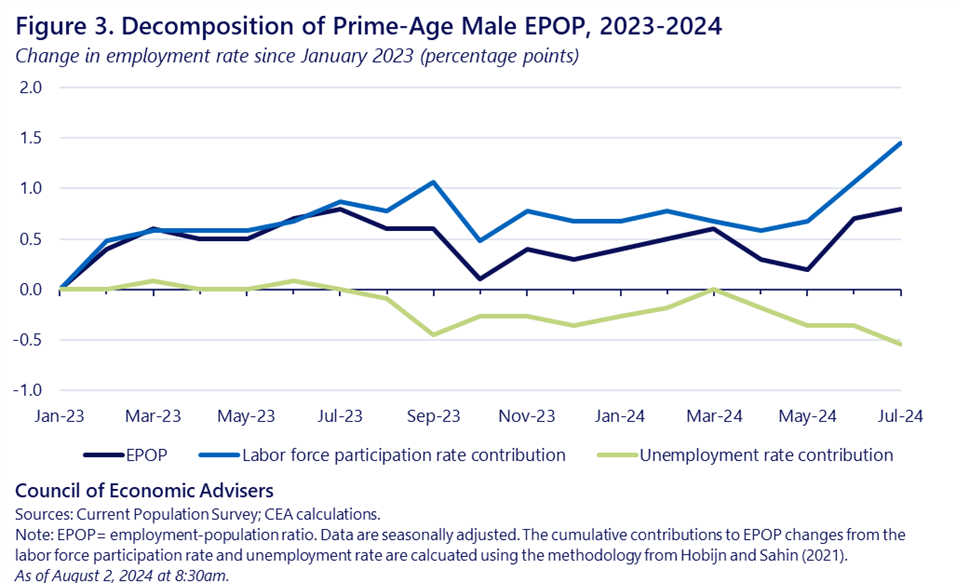

Labor force participation matters for employment rates (i.e., the employment-to-population ratio). Using a simple decomposition technique shown in the appendix, we show that rising men’s LFPR has recently helped to boost their employment rate. [3] The 86.6% employment rate for prime-age men is slightly above their 2017–19 average of 86.0%, which derives in large part, as shown below, from an even stronger improvement in their LFPR (employment rates are lifted by both higher participation and lower unemployment and vice versa).

Figure 3 shows the cumulative change in prime-age male employment, along with the contributions to it from changes in participation and unemployment. Since January 2023, strength in participation has actually offset some weakening in the unemployment rate, sustaining prime-age men’s employment rate at a relatively high level.

Removing barriers to both women and men’s participation in the labor market is a core goal of the Biden-Harris administration, as discussed in the 2024 ERP. It is therefore encouraging to see the progress that both working-age men and women are making in this regard.

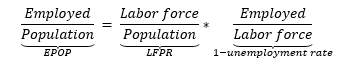

Appendix

The employment rate decomposition below is used in figure 3 to better understand the roles of changes in unemployment and LFPR for shaping the trajectory of the employment rate.

[1] A 2016 CEA report examines this phenomenon in detail and discusses the validity of some often-cited explanations.

[2] For this decomposition, CEA compared the January 2017 through December 2019 period with the period from January 2023 through June 2024.

[3] CEA (2021) used this decomposition to understand the behavior of prime-age employment in previous business cycles. See Hobijn and Sahin (2021) for additional details.