Remarks by CEA Chair Jared Bernstein at the Economic Club of New York

As Prepared for Delivery

I wanted to take advantage of this privilege to speak at the Economic Club of New York to pull back a bit—don’t worry, not too far—from our daily obsession with the dataflow. In my conversation with Mark, I’ll be sure to share with you CEAs and the administration’s near-term economic outlook. But my hope is that you might find it interesting to hear how we in the Biden administration think about some big, contemporary questions in political economy.

Questions like:

What is the role of government in a market economy and how has that role evolved?

Economists agree that market failures occur, and when they do, there is a role for government intervention. But what defines market failure? One perspective on the uptick of current economic policy interventions is that some governments, including our own, are diagnosing more market failures. Is that true, and if so, why?

Is there evidence in support of the prescriptions we’ve put forth to address these failures?

I suspect you’ve heard President Biden inveigh against so-called trickle-down economics in favor of what he calls middle-out, bottom-up economics. This framing introduces the idea of not just market failure but policy failure, invoking the need to replace a misguided economic policy of the past with a better one, where “better” means better micro and macro outcomes—stronger, steadier growth that is more broadly shared.

Our work to accelerate the spotting and correcting of market and policy failures raises some eyebrows, to be sure. A recent New York Times article quoted a deputy chief economist from the World Bank critiquing the pursuit of industrial policies by stating: “There are different ways of shooting yourself in the foot…This is one way of doing it.”

In a recent speech, managing director Georgieva of the IMF argued for caution in this space, warning that “Some of the measures announced or implemented last year were not always clearly related to market failures.” Given the risk of political capture of economic policies, it is a warning to be heeded. Greg Ip of the WSJ recently wondered, reasonably, what was the limiting principle of industrial policy, meaning how and where do policy makers draw lines between public and private activity?

It is thus important to keep the bar high for intervening in market outcomes, but the examples I’m going to share with you handily clear it. In fact, many interventions, especially in the competition space, correct policy failures that unleash more market forces, like recent actions on non-competes or measures to offset unfair trade practices, which, as Michael Pettis recently pointed out, unleash comparative advantages that were otherwise diminished by manipulated trade and capital flows.

Let’s start by reflecting on policy-makers response to the pandemic-induced recession.

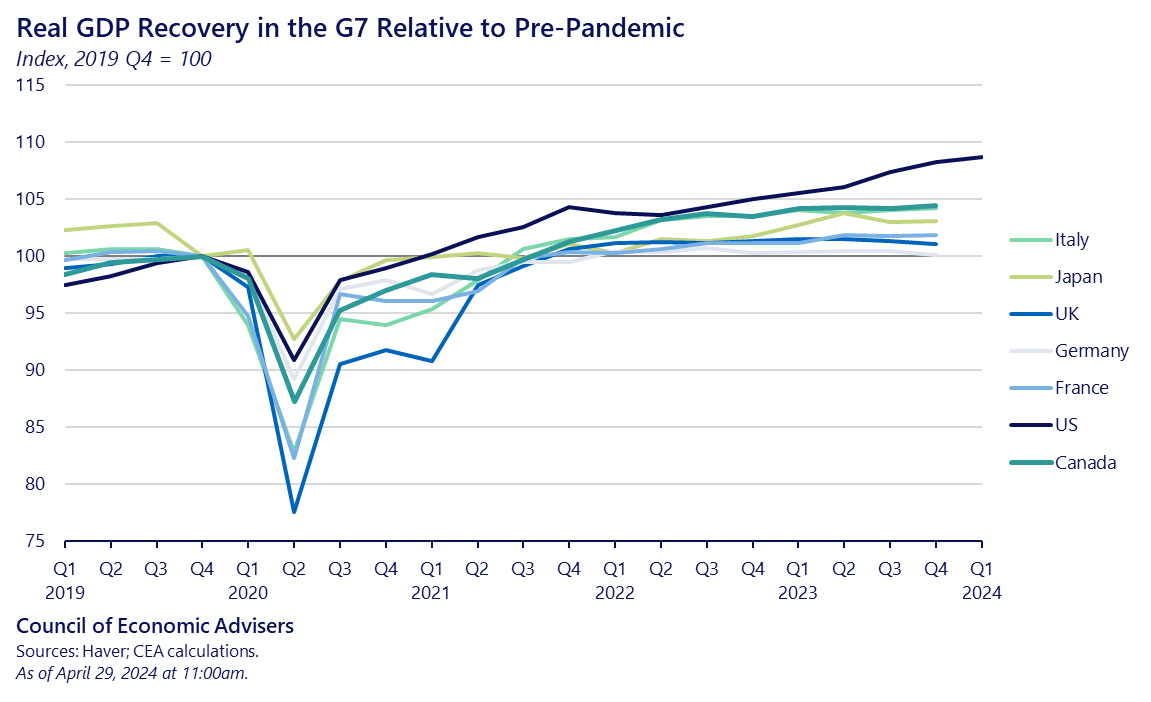

Of course, when GDP craters and unemployment spikes as was the case in the pandemic-induced recession, we’ve known since at least Keynes that there’s a role for countercyclical fiscal and monetary intervention. What’s notable here is that policy makers throughout the advanced economies enacted fast and generally effective policies to offset the shock. The policies took different shapes. EU governments did more to keep workers connected to their jobs. We did some of that but mostly expanded unemployment insurance benefits to the literally tens of millions who were laid off (we also hugely ramped up vaccine distribution). As the first figure shows, V-shaped recoveries ensued, with the US leading the pack.

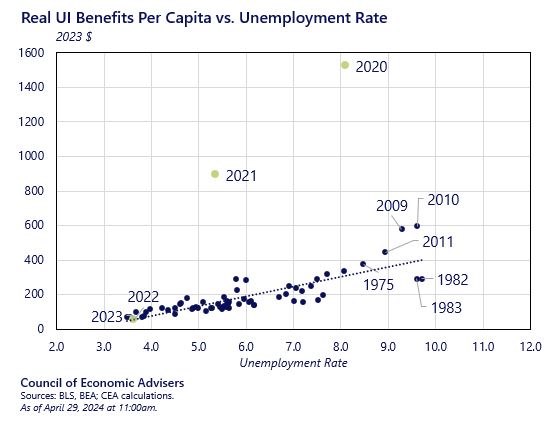

But let me show you two figures that get more at the uniqueness of the U.S. response. The first figure shows how elevated the UI support was relative to our own history, and shows how those benefits coincided with a very quick return to full employment.

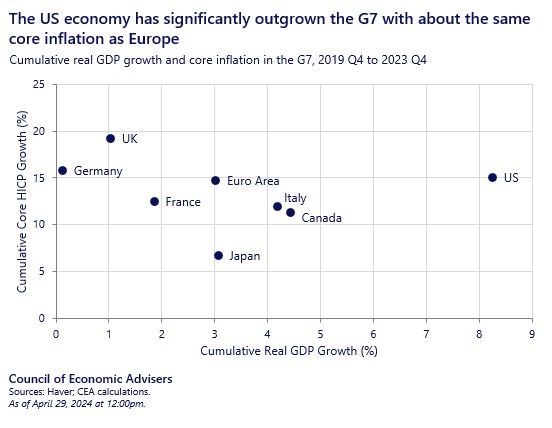

Now, some will reasonably look at that UI figure and say “inflation!” And I’ve long held that the combination of strong demand and constrained supply, amplified by the pandemic-induced shift in consumer preferences from services to goods, led to inflationary pressures. But the next figure shows that cumulative inflation was quite consistent across the G7 economies, all of which employed different fiscal policies of differing magnitudes.

Where the U.S. is an outlier is in real GDP growth. We had similar inflation outcomes as other G7 economies but have enjoyed uniquely positive growth outcomes. Of course, some of those other countries have been a lot more exposed to the war in Ukraine than we have.

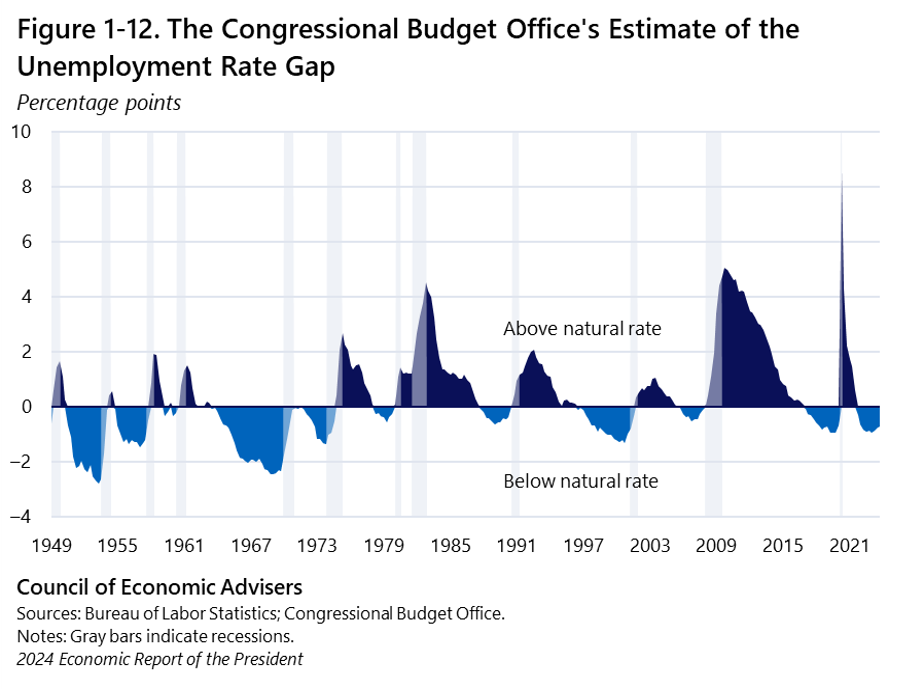

These figures show a cyclical story, but the absence of full employment, has, for the last 40+ years, been a structural shortfall as shown in the next figure. The figure shows that over the first half of postwar history, the U.S. labor market spent 64 percent of quarters with the unemployment rate below the CBO’s estimate of the natural rate. But over the second half of the period, starting in 1982, the United States achieved full employment in 38 percent of quarters, a potent challenge to the assumption that labor markets naturally settle into full employment conditions.

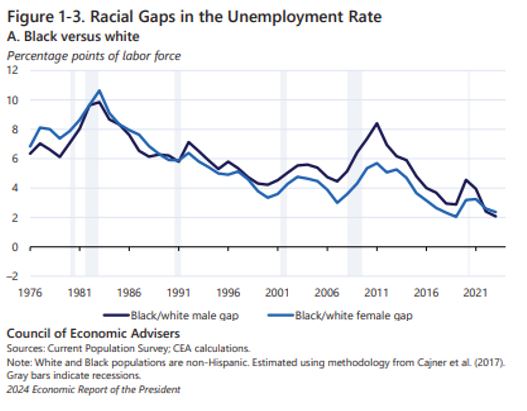

From my many years of working with President Biden, I can tell you that he is acutely aware of the importance of full employment, and the fact that I’ve focused on this market/policy failure over much of my career is one reason we click. The first chapter of the latest ERP goes into great detail of the benefits of full employment and costs of persistent slack, which I’m happy to amplify during Q/A. But as a teaser, I included one figure here showing the powerful impact of tight labor markets on racial unemployment gaps, which recently hit their lowest levels on record.

Extended periods of tight labor markets can lead to reverse hysteresis, or improvements in the economy’s supply side, for example by pulling workers into the labor market who might otherwise be left behind or by improving other supply-side fundamentals, including even productivity. The theory, which has some but not a lot of evidence, is that when full-employment labor markets boost labor costs, less efficient firms are forced to discover new efficiencies to maintain their unit labor costs and thereby their profit margins.

That’s sound logic and I hope it’s true, but the broader punchline here is labor markets do not necessarily settle into full employment and the absence of these conditions is starkly counter to our worker-centered agenda.

Let me turn to another obvious market failure: inadequate investment to mitigate climate change, which has served as a motivator for our industrial policy as market forces alone have not yielded sufficient progress on shifting our economy from a fossil fuel-based energy system to one based on clean sources of energy. For relatively proven technologies such as solar, IRA-style production tax credits can lower the cost of adoption. Such support is not about picking winners, but rather about sending lasting demand signals that allow private industry to make clean investments. A key principle that CEA has elevated in this context, one that speaks to Ip’s question about limiting principles, is that once these technologies achieve cost parity and become cost competitive with emitting energy sources, government intervention can dial back.

The costs of inaction are already present—last year saw a record 28 weather- and climate-related disasters in the U.S. causing losses of over $1 billion per event—and the probability of lasting damages to human health, food insecurity, social instability rises if we fail to meet our targets. But there is also enormous upside to the transition: by targeting clean energy resources, our economy could unlock lower energy prices, greater energy security, and create new industrial sectors centered around innovation and production of new energy technologies.

With an upbeat investment tempo that has surprised many of us, targeted support for clean energy technologies is clearly pulling in significant private investment. Since President Biden took office, private firms have announced more than $500 billion in new manufacturing facilities in the United States, including in solar, wind, batteries, and electric vehicles.

Next, let’s turn to trade policy, where the intellectual evolution among some economists has been particularly nuanced. Summarizing broadly, trade and political economists have historically viewed expanded trade flows—and their corresponding capital flows—as unequivocally positive, as they lowered consumers costs, expanded the economy’s supply side, extended the reach and depth of financial markets, and, if you listen to rhetoric around 2000, prior to China’s accession to the WTO, even inculcated democratic values.

There’s solid evidence for some of those claims. But they overlook distortions that I learned about back at the Economic Policy Institute in the early 1990s, when we were perennial skunks at garden parties, warning about what came to be called the China Shock. While recognizing the benefits of expanded trade, we also saw that some of our trading partners, most notably China, had persistent surpluses that stemmed from management of both currency values and their consumer-spending share of GDP, a key variable that has long been suppressed. Anyone willing to look at these dynamics quickly saw that the old textbook, identity-based explanation for trade deficits—profligate countries under-saving relative to their production and consumption—was insufficient to understand what was happening in global trade.

We now know that if a trading partner suppresses their own internal consumption, then exports their excess savings and excess capacity our way, such unchecked flows can wreak havoc ranging from financial bubbles—see Bernanke’s global savings glut work circa 2005—to the hollowing out of high-value-add jobs in communities exposed to these forces.

Ignoring warnings back then has turned out to be costly to America. Communities lost crucial, anchoring businesses, often in manufacturing. When they complained about the impact of globalization, they were met with woefully insufficient offsets and perhaps even worse, a promise from political and policy elites that the next trade agreement was going to work out much better for them than the last one had. We are still very much in the throes of the economic and political fallout from those days.

In the context of my comments today, we know that trade generates both positive and negative externalities, invoking a role for gov’t to boost the former and dampen the latter. We at CEA have worked hard to elevate this both/and perspective, balancing both trade’s benefits and costs when considering policy.

Most recently, you see these dynamics in play in discussions that Secretary Yellen had with Chinese counterparties during her recent visit. Based on the industrial policy rationale described above, the risk that China could manufacture and export excess capacity of heavily subsidized goods into sectors like EVs and clean energy, upending our domestic investment plans, must be viewed as a risk of China Shock, part 2.

Yes, people are consumers who benefit from positive terms-of-trade. And domestic businesses benefit and grow more quickly than they would otherwise due to a deeper supply of intermediate inputs. There’s even evidence that more trade boosts the productivity of firms who face broader competition. These are all benefits of trade that we continue to pursue.

But people aren’t only consumers. They’re also workers who seek not just incomes, but dignity from their jobs. I like to think that economists have moved beyond the simplistic assumption that all you needed to know about trade flows is that they lower costs.

Finally, partly in honor of Mark, I will discuss a market failure that looms particularly large in both the Biden administration and the public’s thinking right now: the long-term shortfall in affordable housing. It is a shortage that evolved over the last two decades, and by tracking the extent to which housing supply has failed to keep up with household formation, we estimate its magnitude to be north of 2 million.

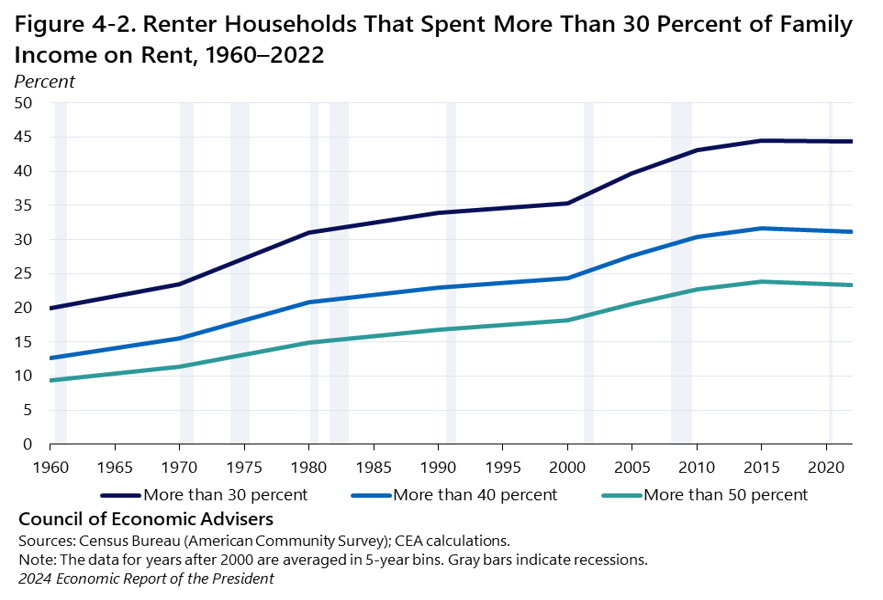

As a result, the figure below shows that 45 percent of renters are now cost-burdened, meaning that they spend 30 percent or more of their family income on rent, more than twice the share who were cost-burdened in 1960.

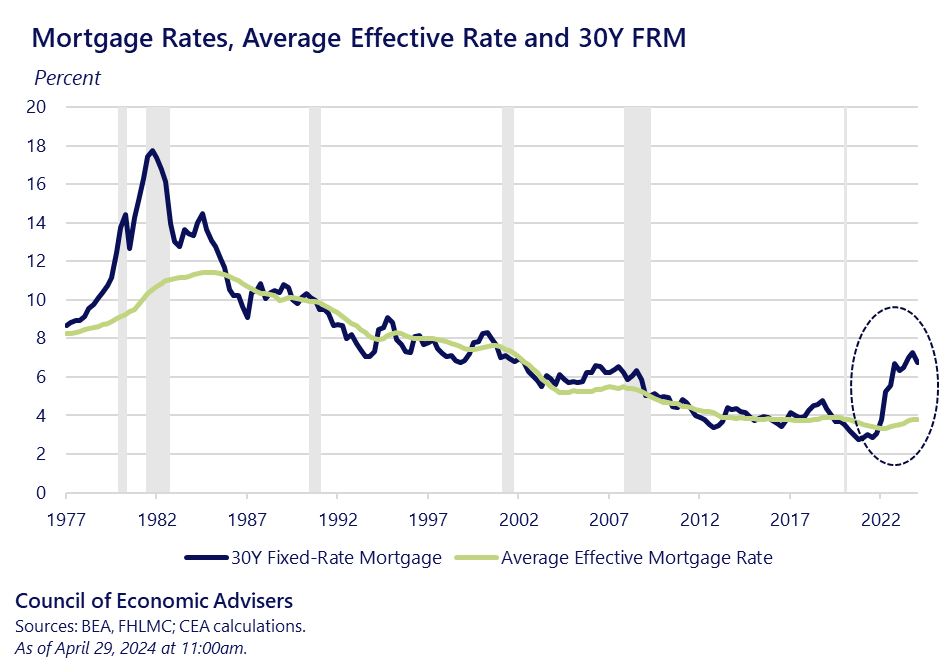

As you see, this problem has been growing for a while now, but more recently, it has been exacerbated by a lock-in problem, a cause of which is seen in the figure below.

This one shows the effective mortgage rate—the average of outstanding mortgages—against the rate of a new mortgage. That spread at the end of the figure is at a 40-year high, and it means people who’d like to move are locked into their lower mortgage. That dynamic, in turn, is significantly reducing housing market churn, and making the first rung of the ladder unreachable for too many families.

Part of this market failure stems from the fact that housing markets are partially regulated by local governments that understandably consider the preferences of resident homeowners and developers, both of whom prefer higher land values. And it’s true that land-use and zoning that can be a reasonable part of community planning—separating industrial areas from schools and residential areas, for example—but they can also reflect historical racial exclusion and they can lead to overly tight restrictions on where and how we can build housing. In that sense, they’ve surely contributed to the supply shortage.

Mark and our friend and housing expert Jim Parrott often reflect on scare land as part of the “pencil out problem,” a related market failure in this space. The problem is that given the costs they face, too often it doesn’t make economic sense for housing developers to build affordable housing.

In response, we’ve developed ambitious plans which we believe would support the creation of 2 million units of affordable housing. Part of the plan is direct subsidization of affordable unit construction through programs like LIHTC and the HOMES renovation project. LIHTC has funded 20% of all new multifamily units since the late 1980s, creating more than 3.5 million affordable rental units. It has the unique advantage of being favored by builders, bankers, and low-income housing advocates, making it a strong candidate for bi-partisan support. We also propose a new Neighborhood Homes Tax Credit to support building or renovating affordable homes. The credit hits the “pencil out problem” by covering the gap between the cost of construction and the sale price.

To try to nudge open some zoning restrictions, we offer bidders a higher ranking on infrastructure and other supports if their application includes a plan to pushback on exclusionary land-use. And we’re continuing to look for ways to advance the production and preservation of accessory dwelling units and manufactured homes.

I can tell you with 100% confidence that President Biden considers building more affordable housing one of the most important pieces of unfinished business in our economic agenda, and one we won’t stop fighting for until we close that gap between household formation and available, affordable housing.

I hope I’ve given you a sense of the worker, family, and community centered-lens through which we view market and policy failures and the role of gov’t in addressing them. Thus far, the track record looks positive in terms of hitting and staying at full employment, helping to stand up critical, domestic industries to fight climate change and ensure more resilient supply chains, pushing back on the exporting of excess capacity to some of those key industries, and deriving a robust agenda to increase the supply of affordable housing.

Our work is far from done—no victory laps here. And there’s more unfinished business besides the housing shortage, including an equally important shortage of affordable child care. But as I’ve emphasized, in many of the areas in which we’re intervening, we’re seeing welcome evidence of middle-out, bottom-up growth on behalf of working Americans.