The Anti-Poverty and Income-Boosting Impacts of the Enhanced CTC

It is well-established that the temporary Child Tax Credit (CTC) expansion that President Biden signed into law helped drive child poverty to a record low of 5.2 percent in 2021, and that the failure to extend the expanded CTC caused child poverty to spike in 2022. However, analyses differ on how much the expanded CTC was responsible for the reduction in child poverty. This blog shows that many CTC analyses understate the CTC’s effect by making across-year rather than within-year comparisons.

CEA’s analysis finds that if the enhanced CTC had been in place in 2022, the child poverty rate would have been 4.0 percentage points lower, equaling 3 million fewer children living in poverty, consistent with other analyses. The expanded CTC’s expiration after 2021 is responsible for more than half of the observed child poverty increase in 2022. This analysis underscores the urgency of reinstating the expanded CTC, as a large body of evidence shows that reducing child poverty reduces hardship and leads to numerous long-run benefits among children, their parents, and their families.

CTC Policy Developments

The CTC was first enacted in 1997, and Congress has expanded it several times in legislation under both Democratic and Republican Administrations. Under the parameters established by the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, the CTC maximum is $2,000 per child and families with no income tax liability can receive a credit of up to $1,500 per child as a refund, making the CTC a “partially refundable” tax credit. Because the CTC is not fully refundable, about 24 million low-income children receive a smaller credit than middle class families because their families’ earnings are too low. Currently, CTC benefits phase out for married taxpayers with income greater than $400,000 and unmarried taxpayers with income greater than $200,000.

The 2021 American Rescue Plan under President Biden temporarily increased the maximum benefit to $3,000 per child for children ages 6–17 and $3,600 for children under age 6. It also made the credit fully refundable, meaning that the maximum credit amount was available to all low-income families, regardless of their earnings or tax liability.

When Congress did not extend the expanded CTC at the end of 2021, the credit reverted to the version established in 2017, which is in place through 2025.

Understanding the 2021 Expansion’s Effects on Poverty

The temporary 2021 CTC expansion provided researchers with rich data on the policy’s impact on child poverty. Some estimates compared the 2021 expanded CTC’s anti-poverty effects to the 2020 credit using aggregate U.S. Census Bureau statistics and concluded that the expanded measure reduced child poverty by 3.1 percentage points. Similarly, reports comparing the 2021 CTC to the 2022 credit using aggregate statistics concluded that the expanded credit’s expiration led to a 2.0 percentage point increase in child poverty.

While both effects are sizable, individual-level data demonstrates that the expanded 2021 CTC had greater anti-poverty effects than aggregate, across-year statistics suggest. In fact, the effects from both starting and ending the expanded credit were about twice as large as suggested by these estimates. The CEA’s analysis implies that extending the expanded CTC would reduce the child poverty rate by an additional 4–5 percentage points each year, pulling 3–3.5 million more children out of poverty.

The Census Bureau reported that the refundable portion of the CTC reduced the share of children in poverty for 2020, 2021, and 2022 by 0.8, 4.0, and 2.0 percentage points, respectively. The difference between years was attributed to the American Rescue Plan’s CTC policy change, but other policy changes and changing economic conditions also played a role. Child poverty can change across years for a variety of reasons unrelated to CTC policy changes, such as family and household structure, economic conditions, and various types of expenses. As such, comparisons of child poverty across years conflate CTC changes with other factors that also impact poverty. For example, work and medical expenses increased child poverty by 3.5 percentage points in 2022 compared to only 1.4 percentage points in 2021, and a cross-year comparison does not disentangle the impacts of policy and expense changes.

To isolate the impact of the CTC expansion, CEA estimated the CTC’s impact on poverty within each year. This approach calculates the credit amount families receive under the expanded and existing CTC structures each year and calculates the resulting impact on poverty and income. Because the approach does not compare poverty rates over time, it disentangles the effects of policy changes and other causes of poverty.

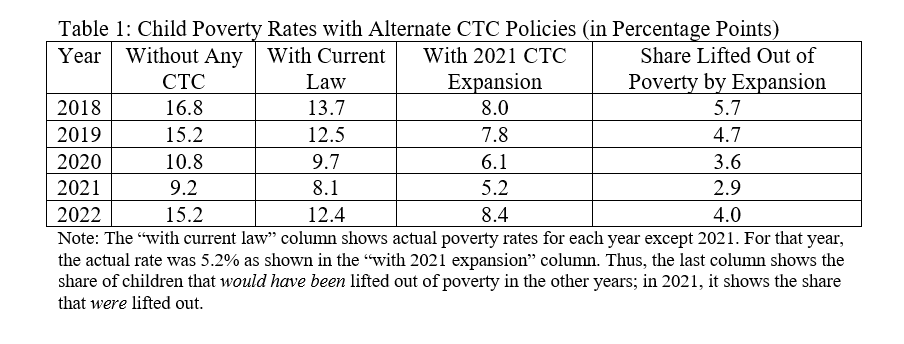

Table 1 shows what the child poverty rate would have been in 2018-2022 if, either, no CTC had been in place at all, current law CTC had been in place, or the 2021 CTC expansion had been in place. The expanded CTC would substantially reduce the poverty rate in every year, and the within-year comparison shows that the expanded CTC would reduce child poverty by 2.9–5.7 percentage points annually.

Removing the Effects of Economic Impact Payments

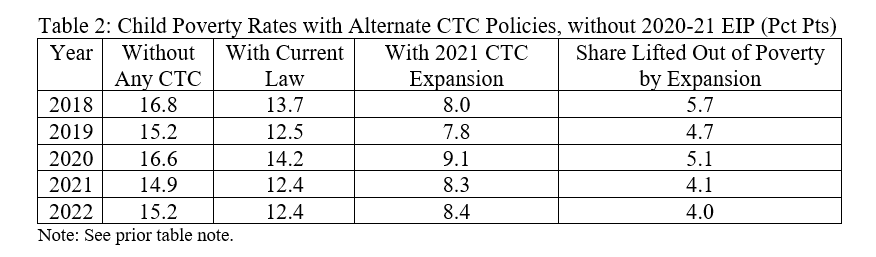

However, it turns out that the expanded CTC’s impact on poverty in 2020 and 2021 was furthermore understated due to the emergency Economic Impact Payments (EIP), also known as “stimulus checks,” disbursed in three increments between April 2020 and March 2021. By raising after-tax income, the payments reduced poverty for some families that would have otherwise been lifted out of poverty by the expanded CTC. Because the EIPs were temporary pandemic-related measures, estimating the CTC’s anti-poverty impact without the payments normalizes affected individuals’ baseline income.

The resulting analysis shows the expanded CTC would have reduced child poverty by 5.1 and 4.1 percentage points in 2020 and 2021, significantly greater than the 3.6 and 2.9 percentage points attributed to the credit when including the effects of the stimulus payments. Overall, a within-year comparison shows that the expanded CTC would reduce annual child poverty by 4.0–5.7 percentage points.

The CTC’s Impact on Median Family Income

While change in poverty rate is an important metric, it can miss economic well-being fluctuations for households on other margins, such as those just above the poverty threshold before receiving CTC payments and those remaining poor after receiving the payments. Examining median income changes is another way to evaluate the policy’s effect.

Between 2021 and 2022, median post-tax real income among households with at least one child 17 or younger fell by $4,256, due in part to their reduction in CTC benefits. Had the 2021 CTC expansion remained in effect, these households’ median post-tax income would have been $2,607 higher in 2022. That is, 61 percent of the median post-tax household income decline for families with children can be explained by the CTC policy change.

Conclusion

If the expanded CTC had been in place in 2022, the child poverty rate would have been 4.0 percentage points lower than it was, equating to 3 million fewer impoverished children. Indeed, the expanded CTC’s expiration at the end of 2021 explained more than half of both the child poverty increase and the decrease in median family income in 2022.

Reinstating the CTC expansion that President Biden signed into law in 2021 would lift millions of children out of poverty every year, which evidence shows would have numerous additional benefits—reduced food insecurity and financial hardship, improved health for children and parents, better school performance, and reduced incidence of child abuse—for children, their parents, and their families. Indeed, the benefits extend into adulthood and far exceed the expanded tax credit’s cost.