Improving Access, Affordability, and Quality in the Early Care and Education (ECE) Market

Nearly 60 percent of children under age six in the United States spend time in nonparental care on a regular basis. For families with young children, access to affordable, high-quality early care and education (ECE)has economic and social benefits for children and their parents. ECE can boost parents’—and particularly mothers’—employment and may alsobenefit children’s short-term development and long-term well-being. These benefits in the long run reap greater productivity, less individual reliance on government transfers, and fewer costly, negative outcomes, such as criminal engagement.

Despite these benefits and widespread reliance on ECE, the market for ECE in the United States does not function well. Rather than a coordinated system, it is a decentralized patchwork of informal and formal providers caring for children—in homes, centers, and schools. While this varied landscape may provide families flexibility to choose the ECE options that best meet their needs, challenges in the market lead to a persistent gap between the cost of providing high-quality care and prices that families can afford.

This post outlines the issues in the ECE market, and the resulting lack of affordable, high-quality care for young children, illustrates how these challenges are particularly acute for low-income families, and highlights policy solutions to expand the availability and affordability of high-quality ECE.

Challenges in the ECE market reduce the availability of high-quality care

Evidence from across the ECE market indicates that it underprovides high-quality, affordable care relative to what families want and what would be socially optimal. Nearly three-quarters of center-based providers experienced excess demand for childcare slots in 2019, and over three-quarters of households that searched for care for their young children in the same year had difficulty finding care that met their needs.

Four primary issues plague the ECE market:

(1) Workforce challenges, including low pay and high turnover, are problematic because child–caregiver relationships and staff continuity are important ingredients in ECE program quality;

(2) The high costs of providing high-quality care because ECE is a labor-intensive industry reliant primarily on families’ payments with limited options for increasing revenue or reducing operating costs to invest in quality improvements;

(3) ECE pricing and consumers’ price-sensitivity may lead families to respond to higher prices by forgoing market-based ECE services and instead relying on informal, unpaid, and often lower-quality care; and

(4) Business model fragility due to many small firms, often sole proprietorships, that face startup costs and thin profit margins, and are particularly vulnerable to economic headwinds.

These market challenges result in less availability of and lower participation in ECE relative to participation rates in other countries and particularly for low-income families.

Use of formal childcare varies across the income distribution

Childcare consumption looks different across the family income distribution. Higher income households are more likely than lower income households to receive and pay for childcare (Figure 1), though there is some subsidization across the income distribution.[1]

The average household that uses childcare for children under six spends $532 per month on it, or eight percent of their income.[2] This estimate includes households that use childcare but do not pay for it. Restricting to the subset of households with young children that pay for childcare, the average household spends $920 per month on it, approximately 13 percent of their income. Lower income households are more likely to receive childcare for which they do not pay, and childcare expenses increase with family income.

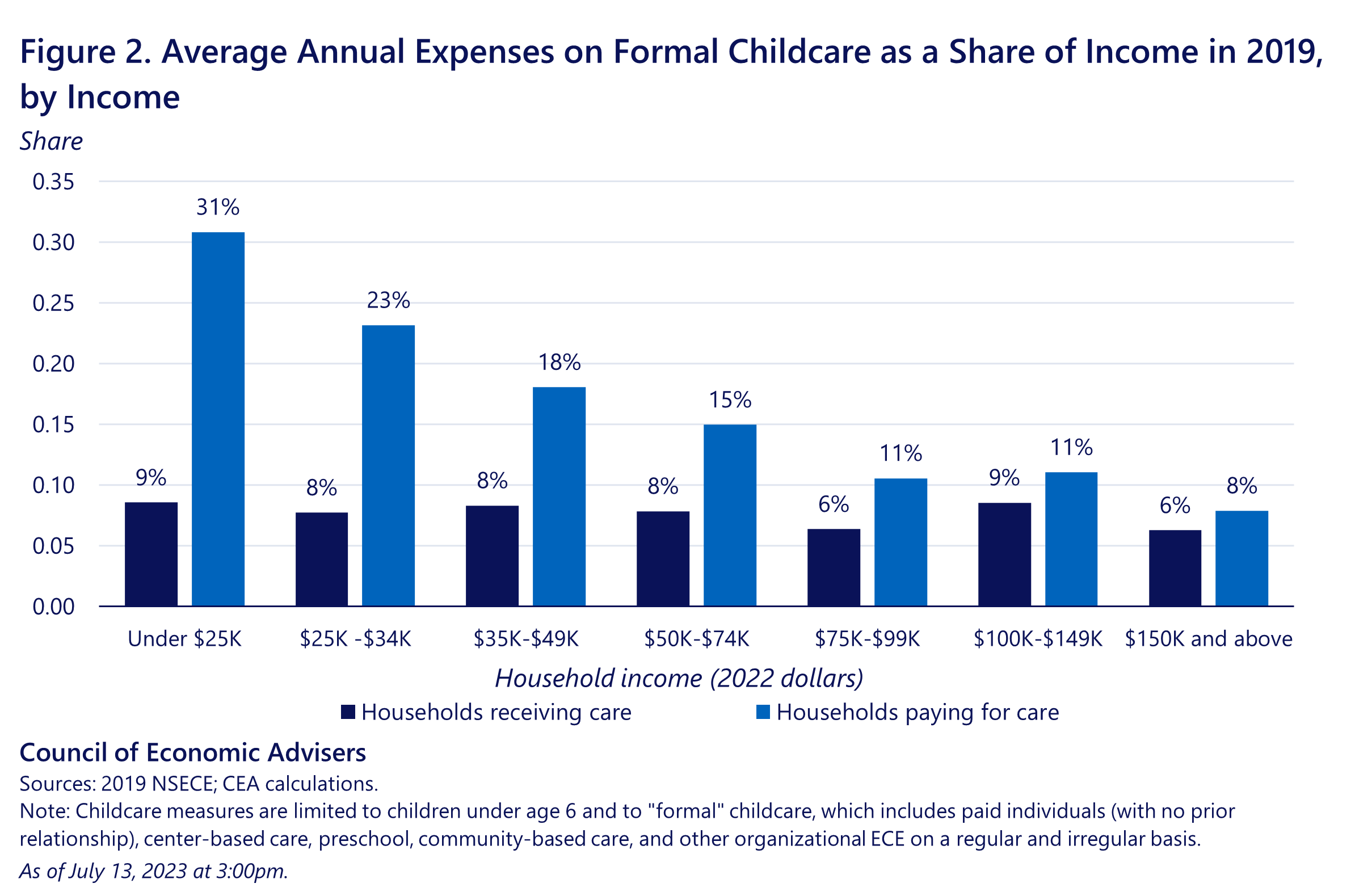

Burden of childcare costs also varies across the income distribution

Growth in childcare costs has outpaced income growth and inflation. From 1990 to 2019, childcare prices rose 210 percent—faster than the overall price index (74 percent) and median family income (143 percent). Among all households that pay for childcare, lower income households pay a considerably larger share of their income for childcare (Figure 2). Importantly, while lower income households would likely qualify for subsidized care—either through childcare subsidies or publicly-provided programs—capacity constraints often mean that participation among eligible families is low. For example, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services estimates that in 2019, 12.5 million children were potentially eligible for childcare subsidies, but only one in six eligible children received them.

Childcare search is more difficult for lower income households

While a majority of young children live in households that experienced difficulty finding childcare, lower income households report greater difficulty finding such care. Over 70 percent of children in households with income between $20,001 and $40,000 that searched for care reported at least some difficulty finding care in 2019 (Figure 3). In contrast, higher income households are more likely to report problems with capacity (“lack of open spots for new children”) and concerns with quality as primary barriers to care.

Improving access, affordability, and quality in the ECE market

Addressing the market challenges in childcare requires policies that close the gap between the cost of providing high-quality care and the prices that families can afford. One such policy is the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF), the federal grant program administered by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services that subsidizes childcare for more than 1.5 million children from low-income families. This week, the Biden-Harris Administration announced a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (ACF–2023–0003), which aims to improve access, lower costs, and expand choices for families while reducing barriers to participation for childcare providers in the CCDF program.

Subsidies for both families seeking care and providers supplying care play an important role in addressing these market challenges and moving toward greater availability of affordable, high-quality care. Two recent working papers find that a combination of subsidies targeting low-income families coupled with provider-side investments proves effective in expanding enrollment in high-quality care. Supply-side subsidies tied to the costs of providing high-quality care allow providers to invest in costly quality improvements, while adjusting the price consumers pay based on their income makes it easier for families to accommodate high-quality care in their budgets.

Improvements to CCDF are one policy lever to support low-income families in their access to care. Greater investments in both ECE providers and families seeking care well up the income distribution—as in the President’s FY24 budget proposal—could make progress in closing the gap between the high cost of high-quality care and the prices families can afford, generating benefits for those families, their children, their communities, and the overall economy.

[1] Analysis of the National Survey of Early Care and Education (NSECE) focuses on formal child care, which includes care provided by paid individuals (with no prior relationship to the household), center-based care, preschool, community-based care, and other organizational ECE on a regular and irregular basis.

[2] This estimate is per household, not per child. When households have multiple children under six, it aggregates their child care expenses. Estimates are in 2022 dollars.