Expanding Economic Opportunity for Formerly Incarcerated Persons

In Chapter 5 of the recently released Economic Report of the President (ERP), CEA discusses economic inequality driven by non-competitive labor markets, and racial and gender discrimination. In recognition of Second Chance Month celebrated annually in April, this blog focuses on one vulnerable group particularly affected by discrimination: formerly incarcerated persons (FIPs).

The Burden of Incarceration

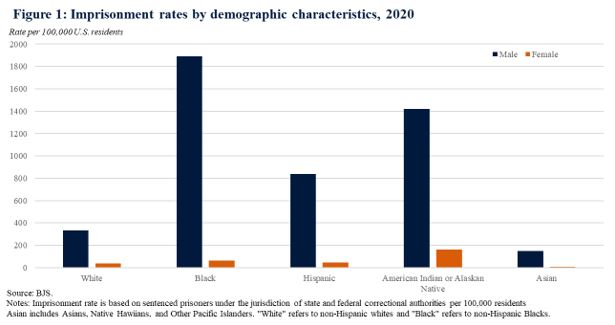

In the United States, people of color are disproportionately incarcerated, due in part to discrimination in law enforcement and legal systems. The disparities are stark. Hispanic men are more than twice as likely as white men to be incarcerated, while American Indian or Alaskan Native men are four times as likely to be incarcerated than white men (Fig. 1). Among all men, Asian men have significantly lower rates of incarceration, at a rate about one-tenth of that of white men.[1]

The disparate burden of incarceration is especially acute for Black men, who are about six times as likely to be incarcerated as white men. All told, as of 2010, nearly 1 in 3 Black men have felony convictions. These astronomical figures are largely due to the nearly four-fold increase in the incarceration rate from 1970 to 2007. Leading scholar Michelle Alexander has deemed this dramatic expansion of the carceral state “the New Jim Crow,” arguing that mass incarceration replaced segregation as a method of social control over Black people.

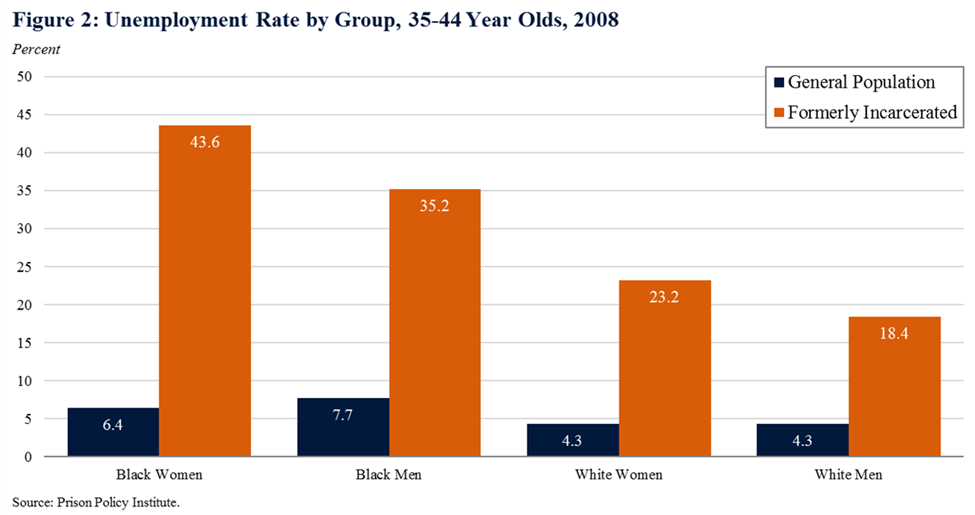

Individuals with criminal records face substantial challenges in the labor market. One 2008 study estimates that the unemployment rate for FIPs in that year was about 27 percent, compared to just over 5 percent for the general population. Figure 2 shows the unemployment rate for formerly incarcerated Black women was about 43 percent, compared with 5 percent for their never-incarcerated counterparts; for formerly incarcerated Black men, the unemployment rate was 35 percent, compared with 6 percent for their never-incarcerated counterparts. The unemployment rates for formerly incarcerated white women and men were 23 percent and 18 percent, respectively, as opposed to 4 percent for their counterparts who were never incarcerated. A Black-white gap in unemployment exists across all demographic groups, but having a criminal record exacerbates the difference, increasing the Black-white unemployment ratio from about 1.5 for never-incarcerated women and 1.8 for never-incarcerated men, to about 1.9 for both male and female FIPs.

Employment is a key ingredient in avoiding recidivism; one study found that those who were released from prison during weak labor markets were significantly more likely to return to prison, with larger impacts for Black releasees and first-time offenders. And for those who are able to become employed, FIPs earn, on average, only 53 percent of the wages of the average worker immediately following release; the lifetime earnings loss for formerly incarcerated persons averages $500,000.

Incarceration as Structural Racism

Labor market discrimination is at the core of the FIP labor market experience. There is substantial evidence of labor force discrimination against formerly incarcerated persons, both due to concerns about recidivism and gaps in work experience, as well as a general stigma above and beyond productivity-related factors. This discrimination is at times codified in restrictions that keep them from working in certain sectors; a number of States deny occupational licenses to those with a prior arrest or conviction.

These forms of discrimination can constitute a form of structural racism, as discussed in depth in Chapter 5 of the ERP. Some forms of structural racism involve overt discrimination in one sector or area that can spill over to another area. For example, Black, Hispanic, American Indian, and Native Alaskan communities are overpoliced and so their members will have higher rates of incarceration; thus, labor market discrimination against the formerly incarcerated interacts with bias against communities of color in policing.

Other forms of structural racism involve seemingly race-neutral policies that can have disparate effects across racial groups. For instance, State laws that deny occupational licensing to formerly incarcerated individuals will disparately impact people of color, even though the laws are not explicitly race-based.

Policy Solutions Must be Comprehensive

A natural solution is to limit an employer’s ability to identify those who are formerly incarcerated. Perhaps the most significant recent attempt to rectify such discrimination are efforts to “ban the box” (BTB), which prohibits hiring managers from inquiring about applicants’ criminal history until after a conditional employment offer has been extended. In December 2016, the Obama Administration applied BTB hiring regulations to all Federal agencies. Congress made BTB law across all of the Federal government, including Federal contractors, in the Fair Chance to Compete for Jobs Act of 2019. In addition, numerous states and localities have enacted BTB laws, which vary in coverage; some apply only to public sector employees or government contractors, while others target all private employees or those in companies of a certain size.[2]

The empirical evidence shows that BTB initiatives have mixed effectiveness. In the public sector, the best available evidence suggests BTB regulations led to an increase in employment among FIPs. This study, which focused on all people with a prior conviction, compared the likelihood of being employed in the public sector in States or counties that implemented BTB policies for public sector employees, as compared to places that had not. The probability of employment in a public sector job increased by 30 percent among those with prior convictions in jurisdictions that introduced BTB.

However, when examining the impact on employment more generally, in public and private jobs, BTB policies are found to have an unintended consequence: large decreases in employment among young Black men with low educational attainment, the demographic with the highest fraction of FIPs. Even though the majority of BTB policies are focused on public employers, private-sector jobs may also be affected by public sector BTB policies, as some large employers voluntarily adopt these policies, and also because both types of jobs interact with each other in the same labor market. Yet, while some subgroups—including younger working-age Black and Hispanic men with no college diploma—face employment reductions after BTB, other groups see increased employment (namely older prime working-age Black and Hispanic men with no college diploma) for whom any prior convictions may be less recent and less of a concern.

Why would employment for certain subgroups decrease after BTB policies are introduced? Evidence from a résumé study in New York and New Jersey suggests that, after BTB, private employers discriminated against most young Black men, in lieu of being able to discriminate against only FIPs. Researchers sent fictitious job applications, varying the characteristics of the job applicant—including race and prior conviction status—and then observed the callback rate for different types of applicants. The study finds the Black-white difference in callback rates post-BTB was greater than the Black-white difference in incarceration rates, suggesting that employers relied on biased stereotypes about Black men as a crude, and highly inaccurate, manner of screening for conviction history.

The differences in results across some of the above studies may be due to a number of reasons: a) the first study focuses on all workers with a prior conviction, while the other two focus on young Black and Hispanic men with low educational attainment; b) the first study focuses only on public employment, while the others include private sector employers. Public sector jobs may face tighter regulations, limiting the ability of employers to resort to using race as a factor in hiring.

Despite the mixed results of these earlier studies, there is more recent evidence that BTB policies can be the cornerstone of a comprehensive strategy to reduce discrimination against FIPs. As an example, one study finds businesses subject to BTB regulations are 28 percent more likely to hire FIPs when offered a single performance review from a past employer; a limited background check covering just the past year; or crime and safety insurance, which features a monetary payout if a FIP commits a crime that adversely affects the employer. Thus, a strategy to bring about more equitable outcomes for FIPs will also require addressing the underlying reasons that employers discriminate against them. This includes continued enforcement of anti-discrimination laws, such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which created the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, as well as the Fair Labor Standards Act.

The Biden-Harris Administration recently announced a comprehensive strategy to support the formerly incarcerated as part of Second Chance Month. The strategy includes the launch of a Department of Justice and Department of Labor job training and reentry service program, marking the first time these programs have been offered to Federal prisoners. In addition, more than 20 administrative actions across different agencies will expand opportunities in areas of training, access to business capital, Federal employment opportunities, and access to federal benefits. The overriding vision of these efforts is summarized in a published strategy on employment opportunities for FIPs.

Supporting FIP employment represents an economic opportunity, not only for the justice-involved persons, but also their potential employers. Some evidence suggests justice-involved employees have higher retention rates and are more motivated to perform highly. FIPs need to be given a fair chance to prove themselves in the labor market. Comprehensive policies that address the discrimination of these workers, while also guarding against potential unintended consequences, play an important role in offering such a chance.

[1] While the incarceration rates of men greatly exceed that of women, there are racial disparities for women as well. Namely, American Indian or Alaskan Native women have significantly higher rates of incarceration than women in all other groups.

[2] Some states enacting BTB regulations include CA, CO, CT, DC, DE, HI, IL, MD, MA, MN, NE, NJ, NM, OR, RI, VT, WA.