The Employment Situation in December

By Chair Cecilia Rouse

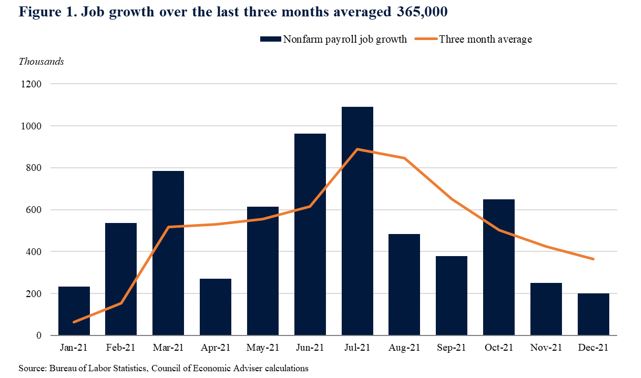

Today’s jobs report shows that the economy added 199,000 jobs in December, for an average monthly gain of 365,000 over the past three months. The number of jobs added in December came in below market expectations. Job gains in October and November were revised up by a combined 141,000.

In addition, the unemployment rate fell by 0.3 percentage point to 3.9 percent as labor force participation held steady and the employment-to-population ratio reached a new pandemic recovery high. This is the lowest the unemployment rate has been since the pandemic began. Wages rose by 0.6 percent over the month, for an increase of 4.7 percent year-over-year. Wage growth has been relatively rapid in recent months as the economy recovers and employers ramp up hiring.

It is important to focus on data trends across multiple months, because data can be volatile on a month-to-month basis. In addition, these data were gathered before the bulk of the rise of the Omicron variant, which will more likely show up in the January jobs report.

This blogpost also serves as a lookback on the labor market in 2021.

- Average monthly job growth in 2021 was 537,000, a fast pace.

In 2021, job growth averaged 537,000, a fast pace (Figure 1). Job growth was fastest in June and July before moderating to a still solid pace in recent months. Job growth from October to December averaged 365,000 jobs per month (see Figure 1). Since monthly numbers can be volatile and subject to revision, it is important to focus on the three-month average rather than the data in a single month, as described in a prior CEA blog.

Nevertheless, the labor market has not fully recovered: employment remains about 3.6 million jobs (2.3 percent) below the pre-pandemic level.

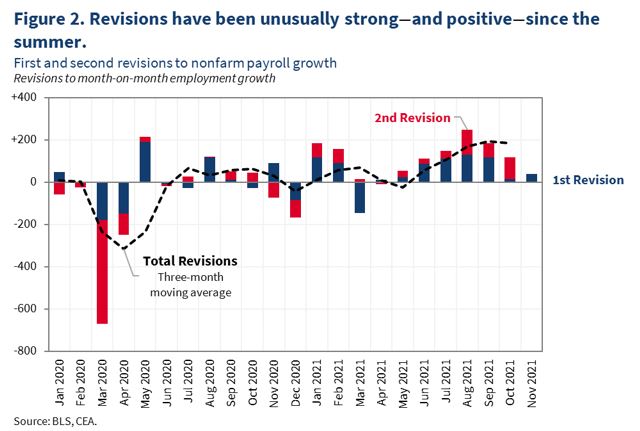

2. Job growth in October and November was revised up substantially, suggesting job growth was stronger in those months than previously estimated.

Job growth in October and November was revised up to 648,000 and 249,000, respectively. Jobs numbers are generally revised twice before they are considered relatively “final.” The combined revisions have been relatively large and positive in recent months, averaging about 100,000 per month so far in 2021 (compared to an average of 8,000per month in 2019, before the pandemic) (Figure 2). The size of the revisions in recent months is an important reminder of how difficult it is to collect data and measure the economy during a pandemic.

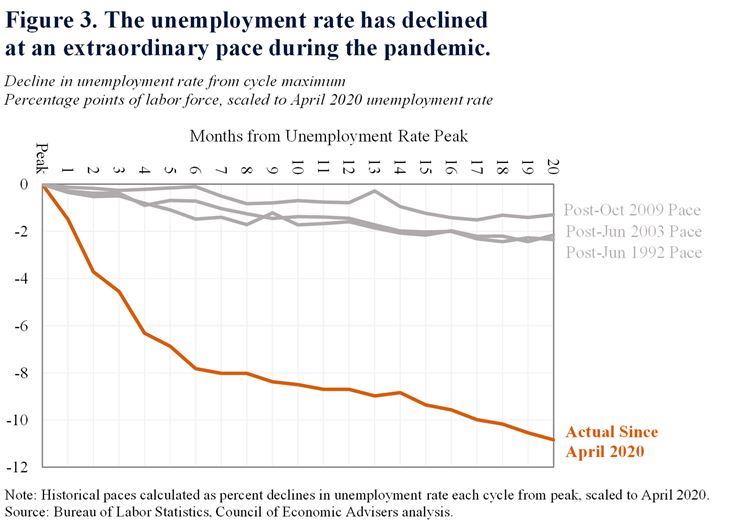

3. The unemployment rate fell dramatically to its lowest rate in the pandemic

The unemployment rate fell by 0.3 percentage point to 3.9 percent, the lowest rate since the pandemic began. This recovery has been unusual in how rapidly the unemployment rate has declined relative to recent recessions (as seen in Figure 3). For instance, the unemployment rate after the 2001 recession peaked at 6.3 percent in June 2003, and 19 months later, the unemployment rate had declined by 1.04 percentage point, a 16.5 percent decline. The pandemic unemployment rate topped off at 14.7 percent in April 2020 and has declined by 10.8 percentage points since then. Had it declined at a similar post-June 2003 pace, it would have declined by only 2.2 percentage points.

Looking back at 2021, the unemployment rate fell by 2.8 percentage points– 2.9 percentage points for white workers and Black workers, 2.3 percentage points for Asian workers, and 4.5 percentage points for Hispanic workers. Small samples sizes for demographic groups can make these measures difficult to interpret.

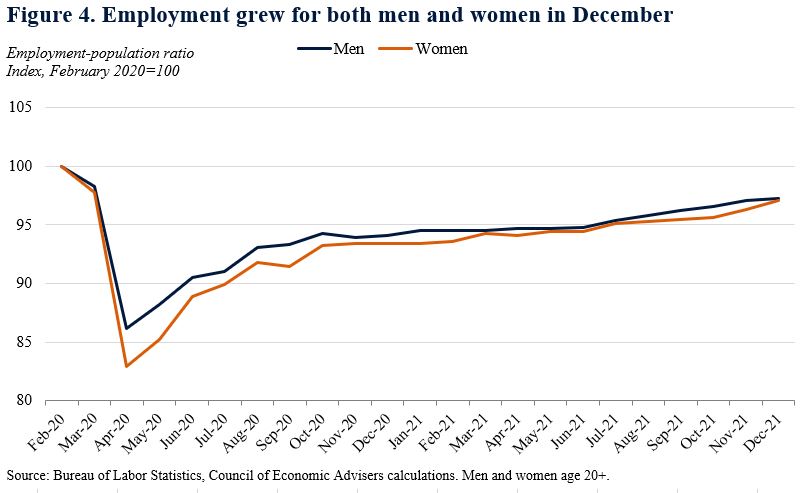

4. The employment-population ratio rose to a new pandemic high, as employment increased for both men and women.

In December, the percent of people who were employed rose by 0.2 percentage point to 59.5 percent. Looking back over the year, in 2021, the employment-population ratio rose by 2.1 percentage points, the fastest 12-month increase since 1984.

In December, the employment-population ratio rose by 0.4 percentage point for adult women, but only 0.1 percentage point for adult men. Indexing the employment-population ratio to the February 2020 level (as seen in Figure 4), the employment-population ratio is 2.7 percent lower than its pre-pandemic rate for men, while it is 3.0 percent lower for women. This gap may reflect that the increased care responsibilities and particular industry mix of this recession and recovery has hit women harder than it has men.

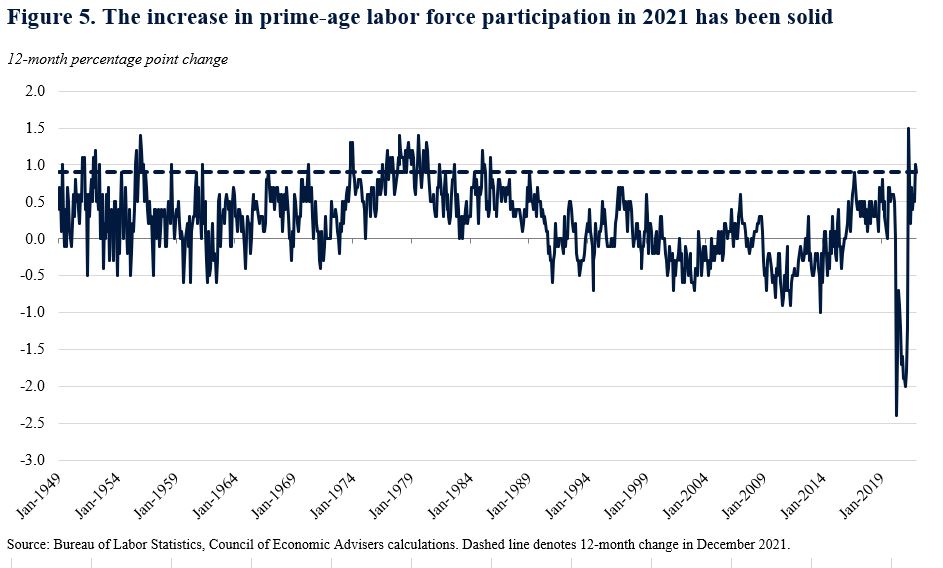

5. While the labor force participation rate held steady in December, in 2021 the prime-age participation rate had its fastest 12-month rise since the mid-1980s.

The labor force participation rate held steady at 61.9 percent in December, as seen in Figure 5. The “prime-age” (25 to 54) labor force participation rate also held steady. It is important to look at the prime-age labor force participation rate because it is less impacted by changes in educational enrollment and the natural slowdown in labor force participation caused by the aging of the population and retirements.

The overall participation rate rose by 0.4 percentage point in 2021 – a strong 12-month increase and the fastest calendar year increase since 1996. The prime-age labor force participation rate rose by 0.9 percentage point, on the higher side of changes in recent years. Prior to the pandemic, the economy had not seen a twelve-month increase in prime-age labor force participation exceeding 0.9 percentage point since the mid-1980s, and had not seen a calendar year increase this fast since 1979.

As the Administration stresses every month, the monthly employment and unemployment figures can be volatile, and payroll employment estimates can be subject to substantial revision. Therefore, it is important not to read too much into any one monthly report, and it is informative to consider each report in the context of other data as they become available.