Alleviating Supply Constraints in the Housing Market

By Jared Bernstein, Jeffery Zhang, Ryan Cummings, and Matthew Maury

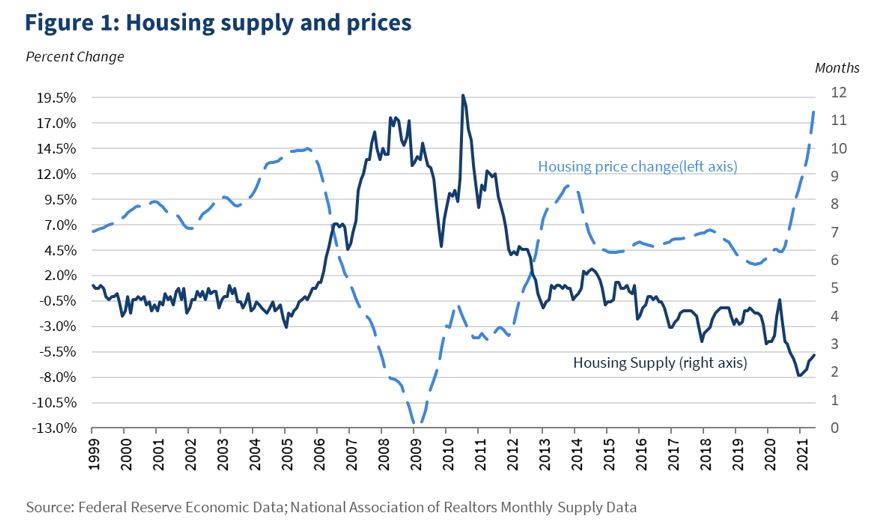

The COVID-19 pandemic shifted families’ preferences for location and type of housing, exacerbating existing supply chain constraints that—for several reasons—have persisted for many years. These pandemic-related changes interacted with the existing housing inventory shortage, resulting in sharp price increases for both owned homes and rental units. Indeed, national home prices, as measured by the Case-Shiller Index, increased by 7 to 19 percent (year-over-year) every month from September 2020 to June 2021. Home prices outpaced income growth in 2020, with the national price-to-income ratio rising to 4.4—the highest observed level since 2006.

While the pandemic may have transformed preferences and caused supply chain disruptions, it did not create the underlying supply constraints in the housing market, which have decreased the stock of rental homes and homes for-sale. The pandemic exposed these constraints that have been around for decades and have impacted households across the income distribution. In the blog, we describe this perennial problem and outline the Administration’s wide-ranging proposals, including those in the Build Back Better agenda, to address the supply shortage and reduce price pressures in the housing market.

Through both legislative and non-legislative measures, these policies have the potential to create or rehabilitate over 2 million housing units, including at least 1 million rental units, based on HUD estimates from past program performance.

Supply Shortages in the Housing Market

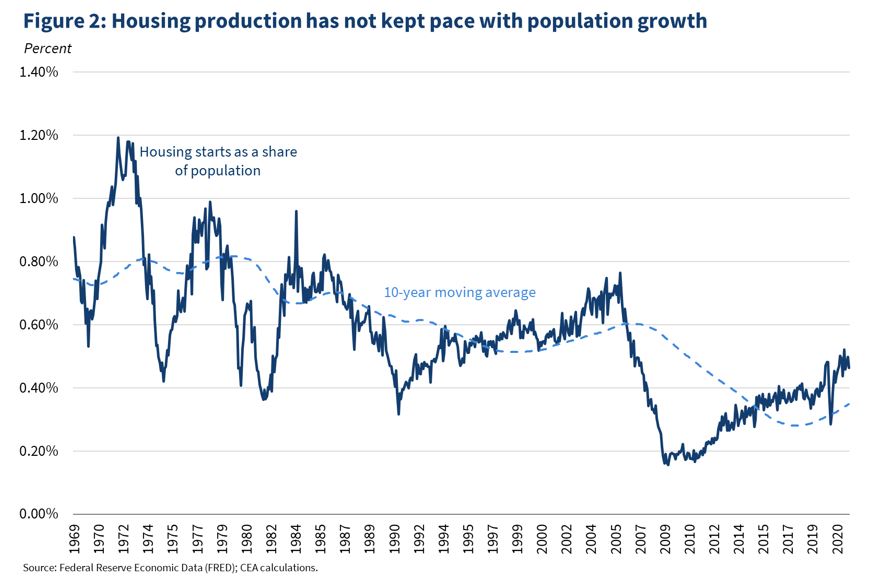

For the past 40 years, housing supply has not kept pace with population growth. A simple way to observe this fact is by looking at housing starts (i.e., new residential construction) as a share of the U.S. population. The figure above shows that housing starts as a share of the population has been on an overall decreasing trend since the 1970s. This decrease became particularly pronounced after the peak of the 2000s housing bubble. Housing starts as a share of the population decreased by roughly 39 percent in the 15-year period from January 2006 to June 2021. Researchers at Freddie Mac have estimated that the current shortage of homes is close to 3.8 million, up substantially from an estimated 2.5 million in 2018.

The above analysis looks at the housing market in aggregate, but there a large and portentous differences between segments of the market. One of the most important is that the number of new homes constructed below 1,400 square feet—typically considered “entry-level” homes for first-time homebuyers—has decreased sharply since the Great Recession and is more than 80 percent lower than the amount built in the 1970s. Similarly, entry-level homes are becoming a smaller fraction of the new homes that are being completed, representing less than 10 percent of all newly constructed homes, compared to roughly 35 percent in the 1970s. These dynamics mean that the critically important “bottom rung” of the home-ownership ladder is far too out-of-reach for young families trying to start building housing wealth.

The dearth of housing supply in the United States is caused by a range of factors and varies between markets. Many urban and suburban markets suffer from a shortage of available land. Part of the shortage of available land reflects public policy decisions of municipalities about how to use land. For example, while the greater Los Angeles area, which is experiencing a housing crisis that disproportionately affects people of color, currently has 84 golf courses (including eight municipal courses in Los Angeles proper) occupying an estimated 10,000 acres of land, a single 200-acre course could potentially provide housing for 50,000 people. Additionally, labor shortages and the cost of building materials have increased in recent years.

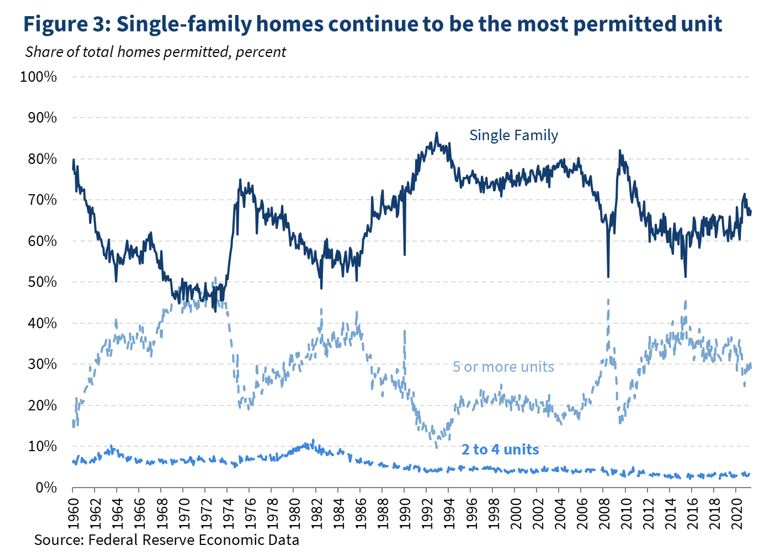

Another key factor driving limited housing supply is local zoning restrictions. For example, rigid single-family zoning, a practice linked with racial segregation, has prevented the construction of multi-family units, which would allow for higher density and an increased supply of housing. One can observe this limitation through the types of housing that have been permitted. As the figure below illustrates, single-family homes account for the majority of homes that receive permits to be built. Roughly 64 percent of all housing that has been authorized since the 2008 global financial crisis has been single-family homes. Units that have two to four residences and allow for multiple families to live on a single lot—as opposed to a large apartment which requires multiple lots to construct—have only accounted for roughly 3 percent of all permits since the financial crisis. Apartments and buildings with more than five units have accounted for approximately the remaining third.

Recently, there have been welcome developments in California and Oregon, at the State level, and Berkeley, Cambridge, Minneapolis, Oakland, and Sacramento, at the municipal level, to change the zoning regulations of these jurisdictions to allow more housing units on various land parcels. These moves offer much-needed potential to increase the housing supply, and are consistent with the Administration’s stance on the need for zoning reform.

In addition to the supply shortage in the homeownership market described above, the United States has an inadequate supply of housing for renters. Across the country, more than 10 million renters (one in four) pay more than half of their income on rent, and nearly half (47 percent) spend over the recommended 30 percent of their income on rent and utilities. From 2012 to 2017, the number of units that are rented for under $600 per month fell by 3.1 million, and the number of units rented for $600 to $999 fell by 450,000. These trends are no doubt partially driven by supply constraints.[1] Rental unit vacancy rates from 2019 to 2021 have been, on average, at their lowest levels in over 35 years. The problem of supply constraints appears to only be worsening. In July 2021, rental prices had increased by 8.3 percent year-over-year, the largest increase for which realty website RealPage has data. In addition, 65 of the country’s largest 150 metros are seeing price increases of over 10 percent year-over-year.

Public housing is also experiencing a supply shortage. Nearly two million people across the country live in public housing, including families with children, older Americans, and people with disabilities. Overall, over 5 million low-income households either live in public housing, privately-owned but publicly assisted housing, or receive rental assistance to find homes in the private market. However, since the 1990s, underfunding and deterioration of the units have decreased the nation’s public housing stock by over 200,000. Given that millions of renters pay half or more of their income on rent, this decline in public housing stock is the opposite of what should have occurred.

These supply constraints in the housing market have an impact on long-term economic growth and inequality. For instance, these constraints increase the cost of housing, which in turn limit labor mobility. Workers cannot afford to move to higher productivity regions that have high housing prices, leading them to remain in lower productivity places. One study finds that this misallocation of labor has led to a significant decrease in the U.S. economic growth rate since the 1960s. Another study estimates that this misallocation could cost up to 2 percent of GDP, which translates to more than $400 billion in lost economic output each year.

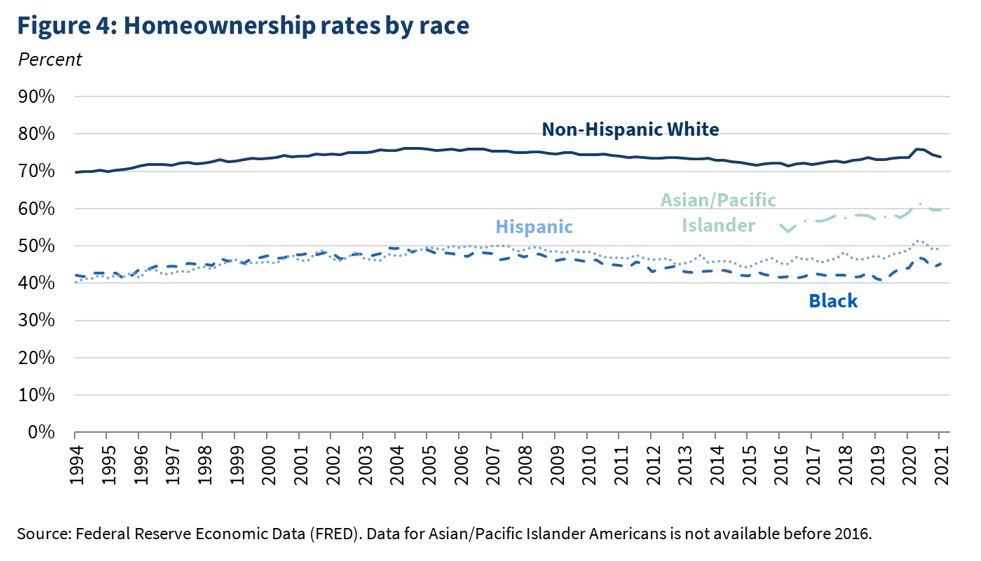

In addition, housing is a key driver of the racial wealth gap, potentially explaining more than 30 percent of the Black-white wealth gap. As the figure below highlights, the differences in homeownership among races has been large and persistent. Since 1994, the percentage of Black and Hispanic Americans who own a home has been roughly 25 to 30 percentage points lower than that of white Americans. For Asian and Pacific Islander Americans, this difference has been roughly 15 percentage points since 2016, when the data first become available. Researchers have found that alleviating supply constraints, which reinforce differences in homeownership rates, would have a significant impact on the racial wealth gap; if Black families were as likely as white families to own a home, median Black wealth would be $32,000 higher. For Hispanic families, equalizing the likelihood of owning a home would increase median Hispanic wealth by $29,000.

Proposals to Alleviate Supply Constraints

Because of their importance to racial equity, economic growth, and living standards, the Biden-Harris Administration has a robust agenda—tapping both legislative and administrative interventions—to address these supply constraints in the housing market.

Administrative Steps

Through coordination with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (“the Enterprises”), FHFA, HUD, Treasury, and State and local governments, the Administration plans to make use of available administrative opportunities to increase the supply of both single-family and multifamily housing. Estimates from HUD, FHFA, and Treasury show that these agencies will create, preserve, and deliver nearly 100,000 affordable housing units over the next three years.

As part of this plan, the Administration will take several concrete steps to ensure that single-family homes held by the Federal government eventually go to owner occupants, or to community-oriented non-profits committed to rehabilitating homes and selling them to owner occupants.

- HUD and the Enterprises plan to increase to 30 days, from 10–20 days, the period in which only non-profits and owner occupants—as opposed to financial market investors—can make offers on the more than 12,000 homes in their Real Estate Owned (“REO”) inventory. These are homes in their portfolio that have failed to sell in a foreclosure auction.

- Further, HUD and the Enterprises will continue to expand outreach to community-oriented non-profits and local governments regarding the sale of federally held homes. Because the Federal housing finance agencies guarantee mortgage repayments, the agencies often have a number of foreclosed homes in their portfolio. Under this new approach, they will cut through red-tape to ensure these properties quickly get on the market, with special access to those most in-need of such assistance.

The Administration also plans to increase financing for manufactured homes and 2–4 unit properties.

- FHFA will authorize Freddie Mac to purchase mortgages for single-wide manufactured homes, thereby extending its 2020 authorization to Fannie Mae. The Enterprises also will continue outreach on financing options for manufactured homes. Such properties have been significantly improved in terms of quality and amenities and, because they are pre-manufactured, they can quickly enter the supply chain.

- FHFA will authorize the Enterprises to take steps to expand the number of mortgages available for purchases of 2–4 unit properties that have an owner-occupant and renters. In so doing, it will be easier for prospective buyers to purchase and build wealth with these properties, and the supply of rental housing can expand as well.

Increasing the supply of multifamily housing is a cornerstone of the Administration’s plan to alleviate housing supply constraints. One proven way to do so is to increase the affordability of financing for building multiunit dwellings, particularly those targeted at low- and moderate-income renters.

- The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) is a tax credit to builders of low-income housing that have a proven track record of increasing the supply of affordable rental units. The Enterprises will build on this record by raising their equity cap for LIHTC from $1 billion to $1.7 billion—from $500 million each to $850 million each.

- Treasury and HUD have formulated a plan to provide affordable financing from the Federal Financing Bank, which is tasked with buying, selling, and originating Federal loans and debt to State Housing Finance Agencies.

- Treasury is making $383 million in the Capital Magnet Fund available for the purpose of encouraging affordable housing production. The Capital Magnet Fund is a competitive grant program for Community Development Finance Institutions and non-profit housing groups.

Legislative Steps

The Administration urges Congress to invest in the construction of affordable housing units, incentivizing the relaxation of exclusionary zoning and helping income-burdened renters.According to HUD, these investments will add or rehabilitate approximately 2 million housing units nationally. In particular, these supply-side policies will:

- Construct or rehabilitate affordable rental housing units using Federal subsidies to support the financing, building, and maintenance of affordable rentals. This would be done principally by expanding the HOME Investment Partnership Program, the Housing Trust Fund, and the Capital Magnet Fund.

- Expand and strengthen LIHTC. As noted above, LIHTC has a proven track record of incentivizing the building of affordable multifamily units. The Administration has proposed to expand LIHTC and target some portion of additional allocations to areas that are particularly supply constrained.

- Build and rehabilitate homes for low- and middle-income homebuyers and homeowners. Based on the innovative and bipartisan Neighborhood Homes Investment Act, the Administration proposes a tax credit subsidy for building and rehabilitating homes for low- to middle-income homeowners living in economically vulnerable communities. Given racial disparities in home values, this proposal advances the Administration’s agenda on racial equity by boosting home values in economically distressed communities, which are disproportionately inhabited by people of color.

- Incentivize the removal of exclusionary zoning and harmful land use policies. One of the most persistent and binding constraints on housing supply is exclusionary zoning laws and practices. For decades, such laws have inflated housing costs, locking families out of areas with more opportunities. Along with working with State and local governments to reduce such restrictions, the Administration proposes the creation of an incentive program that awards flexible and attractive funding to jurisdictions that take concrete steps to reduce barriers to affordable housing production.

Conclusion

There is no magic formula to quickly relieve the supply constraints described in this blog post. Shortages in housing stock along the entire price spectrum and their associated social and economic consequences have been building for decades. However, the proposals set forth by the Biden-Harris Administration—proposals we expect to create or rehabilitate over 2 million housing units—will make critical investments in our country’s housing infrastructure. By adding to the housing stock, and to the useful life of existing housing through rehabilitation investments, this is a once-in-a-generation effort to improve the lives of millions of Americans by making housing more plentiful and affordable.

[1] Low-cost units fall out of the inventory through demolition or are converted to higher-cost housing. It is difficult for the private market to replace low-cost units through new construction without subsidies or incentives, because the cost of constructing new units exceeds the ability of lower-income families to pay the unit cost. It does not “pencil out.”